In Over Our Heads (Again)

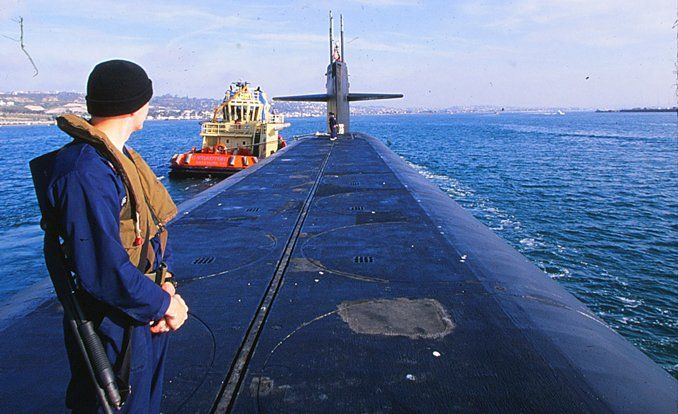

(Click image for Trident ballistic-missile submarine specs.)A Trident ballistic-missile submarine draws 36 feet of water—more than any other Navy vessel save a Nimitz-class aircraft carrier. In San Diego harbor, where the U.S.S. Alaska picks us up, it clears the bottom in some places by only two feet.

“In the event of a water landing,” jokes Navy Lieutenant Kevin Stephens, “alarms will sound. So, uh, stand fast but clear of hatches, ladders, and watertight doors. Stow your tray table in the locked and upright position. Await your EAB.”

“My what?” I ask.

“Your emergency air-breathing apparatus,” he clarifies.

The lieutenant notices my fidgeting. Plus, he notices a second scopolamine patch, affixed limpet-like to my neck.

“Really, nothing to worry about,” he assures. “For instance, in the event of a major earthquake, you’ll find this to be the safest place on the planet.”

A lone porpoise leads the Alaska to deep water.

Which is probably true. That’s because I’ve just climbed aboard the U.S.S. Alaska, SSBN 732, a Trident nuclear ballistic-missile submarine. The Alaska is the seventh in a fleet of 18 missile subs, a group currently packing 54 percent of America’s entire nuclear arsenal. It is a large vessel. As long as the Washington Monument is tall. It is also expensive: $1.8 billion, or the cost of 10 new Boeing 747s. “That makes it C/D‘s most impressive ‘as tested’ price ever,” I tell Stephens. “I suspect our insurance won’t cover the whole amount. What’s your deductible?”

“In that case,” he says, “we won’t let you drive.”

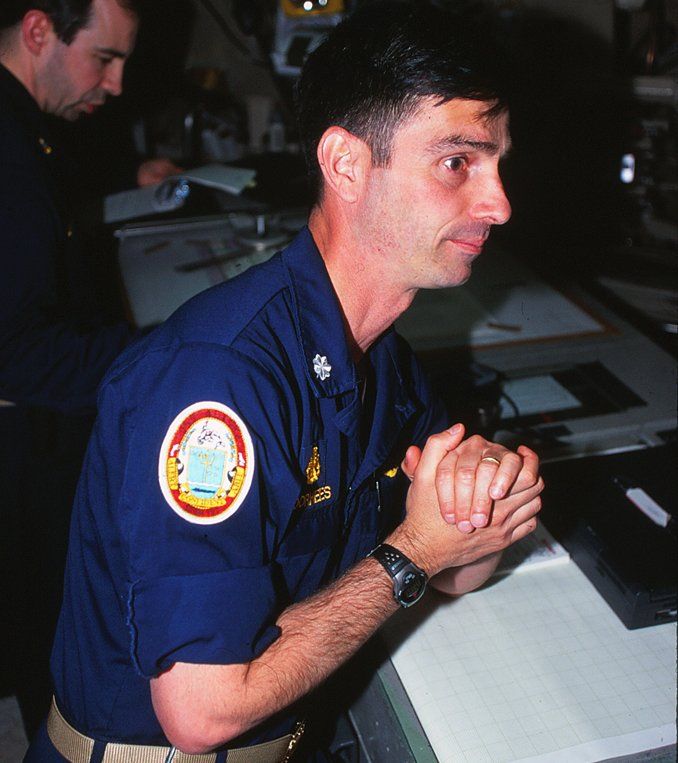

I am officially welcomed aboard by a soft-spoken man with mink-brown eyes and the physique of a long-distance runner. He is wearing blue coveralls and tennis shoes, same as every other crewman. “Enjoy the man-overboard drill?” he asks. That’s when I notice the oak clusters clogging his lapels. This is the captain, 41-year-old Kenneth J. Voorhees, an MBA from Villanova University, an amateur pilot, and a veteran of three other nuclear submarines. Voorhees may be small, but when he passes through the passageways, crewmembers reliably flatten against the walls like Velcro Man. The Pentagon has a saying: The three most powerful men on earth are the U.S. president, the Russian president, and the captain of a Trident missile sub.

“Rig ship for dive, make turns for ahead one-third,” Voorhees barks.

These commands are answered in a blink: “Aye, ship rigged for dive, sir. Maneuvering answers ahead one-third.”

No one boards the sub without an invitation, as the angry armed person ensures.

As the U.S.S. Alaska scythes beneath the waves just outside San Diego Bay, a Klaxon blares, accompanied by a “Dive! Dive!” voice that resembles the “Pull up! Pull up!” voice heard in the cockpits of aircraft flying too low. After that, the control room falls eerily silent, apart from a diving officer calling out our depth. The sub is slow to sink. Ninety seconds after the command to dive, we’re only 56 feet under (measured at the bottom of the hull) — the conning tower is still in sunshine. Once we’re submerged, surprisingly, the Alaska continues to bob and roll — its cigar-shaped hull is as susceptible to currents as a VW bus is to crosswinds. The crewmen speak softly, in part because they’re rarely more than 20 or 30 feet from other crewmen asleep in bunks. And there’s an uncanny absence of engine racket — just the white noise from hundreds of ventilators and computer fans. It’s like sitting aboard a jet that’s idling at the gate, if the jet’s interior were as densely packed with machinery as a locomotive’s.

To ensure the Alaska stays quiet, her machinery is mounted on “rafts” suspended by rubber decouplers. The crew regularly sweeps the boat acoustically to locate “noise violators” — vibrations that have somehow found a path to the three-inch-thick steel hull. “Something as small as a failed bearing in a fan can do it,” Stephens informs. “And we once found a Coke can wedged between a spar and the hull. That did it, too.” Trident subs are so quiet, in fact, that no foreign vessel has ever successfully tracked one. Or so the Navy says.

To reach the sail—also known as the fin, the bridge, the fairwater, and the conning tower—you climb a 45-foot ladder through a passage so narrow that the cylindrical walls grateagainst your hip pockets.

What’s more, no piece of machinery is cleaner. The ’70s-era linoleum — a depressing beige with Hershey-brown spots — nevertheless glistens. No dust, grease, litter, rags, papers, or debris. No fingerprints. No naked-girl calendars, no personal photos, no graffiti. Several off-duty crewmen are wearing slippers. The soles of their feet are cleaner than my Levi’s.

Unlike the 360-foot “fast-attack boats” — the subs made famous in The Hunt for Red October — the 18,750-ton Trident-missile subs don’t hunt for enemy craft. Instead, the 560-foot boomers leave port, submerge immediately, cruise silently at a snail-like five knots, and eventually reach an assigned site where they run around in circles on stealthy “deterrent patrol” until it’s time to sail home. From those secret chunks of watery real estate, all 24 of the Alaska’s nuclear missiles can quickly annihilate their preselected targets. The routes to and from that piece of ocean are plotted so that a boomer will encounter no other U.S. submarine. If another underwater vessel is detected, it is assumed to be hostile. When that happens, however, a boomer will neither investigate nor intimidate. Instead, it will play possum until it can skulk away undetected, thereby remaining free to fulfill its lone mission: launching missiles at land-based targets.

Each of a boomer’s patrols consumes roughly 77 days, during which the sub will not surface, nor will any of its 160 crewmen so much as glimpse sunshine, much less a foreign port. When a missile sub returns — steaming into either Bangor, Washington, or Kings Bay, Georgia — it will spend 35 days taking on material, groceries, refurbished electronics, and an alternate 160-man crew, which will then depart on its own 77-day cruise, never knowing where their boat has most recently sailed.

When Captain Voorhees asks questions, crewmen don’t answer quickly. They answer instantaneously.

The malevolent splendor of a nuclear submarine is that it is theoretically capable of cruising underwater for 24 consecutive years — the duration of the Alaska’s 180-megawatt reactor core — if only it could carry sufficient soup, canned ham, and Planters peanuts to satisfy its crew. The Alaska’s 14-foot-tall General Electric S8G nuclear reactor is used only to make heat, which creates steam that spins geared turbines. The main turbine belts out the 42,000 horsepower necessary to rotate a seven-bladed screw at revs sufficient for a submerged speed of close to 24 knots. The exact top speed is classified, and C/D failed to attach a fifth wheel because dolphins kept knocking it off.

Smaller steam turbines, in turn, make the electricity necessary to illuminate the sub’s passageways and power its 800 refrigeration tons of air conditioning. More important, that juice is used to convert seawater into distilled water — some 12,000 gallons daily. Aboard subs, distilled water is a very large deal. It allows the crew to drink and bathe, of course. But it’s also what the reactor prefers as a coolant, and it can, via a simple process of electrolysis, be converted into a limitless supply of oxygen. In fact, the Alaska’s atmosphere is held at a steady 18.5 percent oxygen, with fewer air-borne allergens and particulates than any business office can boast, making it a great place for aerobic exercise.

The sub’s control room, its nerve center, is dark, cramped, and as filled with guys as a Big Ten bar, although no man speaks until he’s asked a question.

Alas, onboard jogging is discouraged — despite Denzel Washington’s cinematic exertions along the 177-foot passageways flanking the missile tubes — because it’s too easy to fall or crack your head on the ever-present snake’s nest of pipes, valves, fittings, and electrical conduits. Our onboard tour guide, 24-year-old Petty Officer Tony Pinto, had only too recently had his own head stitched up — for the second time — by the boat’s lone medical officer, Juan LaBoy. Minor injuries of this sort are exasperating, says LaBoy. If a sailor is injured and can’t stand his six-hour watch — during the submarine’s traditional 18-hour day — the slack must be absorbed by the two other men trained to share that particular duty, thus increasing their own workloads by 50 percent.

“And to tell you the truth,” Pinto adds, “you’re always tired. [The sailors who clean the sub and repair broken equipment do so during their daily six hours of “free time.”] The rule of thumb is, if you have even 20 minutes before you’re expected somewhere, put your head down.”

Missile silos poke through four floors; you learn to sleep with your skull next to a warhead.

Pinto shows us to our bunks in a nook roughly 10 feet square, only six feet from an orange-brown missile silo. The room is lined by coffin-sized berths stacked three deep on three sides. Within each bunk, there’s a tiny fluorescent light, although there’s barely space to prop a hardcover book on your chest. In fact, whenever I roll over, I slam an elbow into my rack’s roof, causing the crewman above to groan. Each bunk, however, is independently ventilated so that it’s cool, dry, and fresh-smelling.

Onboard entertainment is meager. There’s a flat-screen TV in the crew’s mess, on which any of a thousand 8mm movies can be viewed. During my stay, the crew was enamored of The Matrix, Deuce Bigalow: Male Gigolo, and Sharon Stone’s revealing scene in Basic Instinct, which was being run in slow motion and reverse. There’s a small library crammed with dog-eared paperbacks. And there exist six computers on which video games can be played. Otherwise, the outlet for boredom is a closet-size gym with two StairMasters and a weight-lifting rig.

Sonar operators are the sub’s ears, listening for surface ships, helicopters, rain, ballast-tank bubbles, shrimp, and “the whir of fine machinery.”

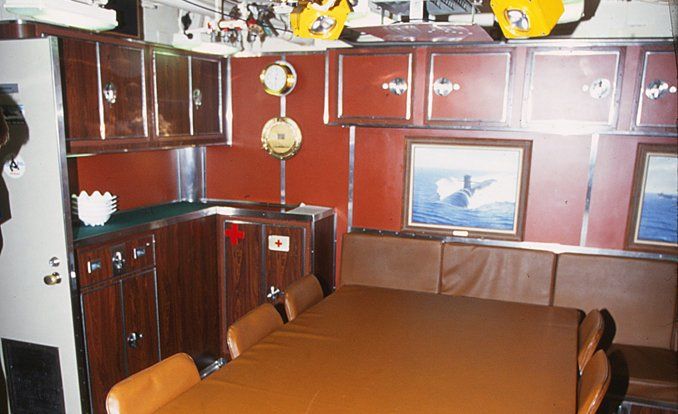

Hot meals are served every six hours in the “Kodiak Cafe,” whose 11 metal tables seat four sailors apiece. If all seats are occupied, you wait in the passageway until a spot opens. Despite what you’ve heard, the food, served cafeteria-style, is adequate, not sumptuous. For lunch, we’re offered cheese sandwiches and macaroni salad. For dinner in the officer’s wardroom – separated from the crew’s mess by a stainless-steel galley the size of a large sauna – we eat tacos and chili. Before supping with the officers, we’re reminded of two points of vital Navy etiquette: First, no discussions involving work, sex, or religion. Second, wait until Captain Voorhees takes a mouthful before so much as unfolding a napkin. Photographer Lorentzen manages to breach this historic point of conduct, but Voorhees, at least outside the control room, is ever calm, smiling, a man at peace.

All that changes inside the control room — the sub’s nerve center — where the 15 men on duty react to the CO as if he were a rattler loose among newborn bunnies. When Voorhees yelps questions, as he does every 20 or so seconds, the answers come so quickly that I’m unsure whether the captain has concluded his query.

“Sonar, conn,” snaps Voorhees, “bearing and distance to Master Eight,” referring to the eighth surface target that the sonarmen are monitoring during that watch.

The officers’ wardroom is the only compartment adorned with anything approaching homey décor. The lone metal dining table is ringed by spotlights so that it may serve double duty as the medical officer’s operating table.

“Conn, sonar, relative bearing one-eight-zero, 10,500 yards, steady at 10 knots, sir,” comes the rapid-fire reply.

“Running navigation lights but no bright lights,” confirms Voorhees as he peers through one of the sub’s two periscopes.

“Tentatively identified as U.S. warship, believed U.S.S. Curts,” says the sonar operator with such fluid confidence that he must surely have anticipated the question. Except that when Voorhees asks him in quick succession about Masters Five, Two, and Six, the replies are equally instantaneous and include new information, such as the location of a cruise ship at anchor 28,000 yards distant. That’s 16 miles.

For the duration of this exchange, the control room is “rigged for red” – bathed in a blood-like glow that preserves night vision and precludes telltale illumination snaking its way up a periscope to reveal the sub’s presence. The sonar operators huddle amid their own otherworldly gloom in a cramped corridor ahead of the control room, their faces painted green by the glow of six CRTs, their ears clamped by bulky headphones. They’re listening for man-made sounds. “The whir of fine machinery – like an electric motor on fine bearings – that’s usually a warship,” says one. “But a clunketta-clunketta, that’ll be a merchant.” They can hear rain. They can hear bubbles bleeding from their own ballast tanks. They can hear helicopters, light planes, and fishing skiffs. “Plus, there are always biologics to listen to. You know, fish, whales, shrimp.” He hands me the headphones, on which I hear only a few clicks resembling an Ameritech long-distance call. “But if you suddenly hear nothing where biologics oughtta be, then you have to ask, Did something big scare all the fish away, something we should worry about?”

Torpedoes are for self-defense only. A boomer would never attack an enemy craft.

No matter how deep the sub dives — and it can allegedly descend to 1640 feet — the Alaska will never willingly pass closer than 4000 yards, or 2.3 miles, to a surface vessel. “One of our jobs is to help [the CO] steer clear,” explains a rookie sonar operator. “We’re like air-traffic controllers, ‘cept we don’t know where the surface craft are headed, plus we can’t ask ’em to move.”

As it submerges, the Alaska releases a 2000-foot whip antenna that floats to the surface, receiving low-frequency radio bursts from as far inland as Omaha. If the right series of three-letter codes arrives – a so-called Emergency Action Message – Voorhees will order an ascent to periscope depth, about 75 feet, then raise a communications mast. In less than three minutes, he can receive 40 pages of confirming data, including the combinations to three safes holding the keys necessary to fire ballistic missiles. With that in hand, the captain will take the Alaska to “hovering conditions” – a depth of about 150 feet and a tortoise-slow pace of 1.5 knots – from which the sub’s Trident D5s can be fired.

Each is a weapon right out of a Jules Verne delirium: seven feet in diameter, four-and-a-half stories tall, 130,000 pounds, a range of 6900 miles. At the apogee of each missile’s route – just as it goes suborbital – it will release 14 separate 150-kiloton “bomblets.” If the Alaska were to unleash her complement of two dozen missiles, she’d have slung skyward more firepower than has been expended in any war in history. “Those missiles don’t rely on terrain mapping to find their targets,” reminds a weapons officer. “That’s because – and I don’t mean for this to sound morbid – we’ll already have so drastically rearranged the enemy’s terrain.”

About the only real onboard entertainment is a flat-screen TV on which any of about a thousand 8mm movies can be viewed. Sharon Stone is a crowd pleaser.

The missile-launch room resembles Houston’s Mission Control Center, with row after row of six-foot-high computers extending 25 feet forward of a limousine-size panel. Before a launch, engineers must first ensure that the weapons’ silos afford perfect temperature and humidity to sustain rocket-fuel ignition. Then they’ll “spin up” the gyros in each inertial guidance system – a process requiring 15 minutes – and pressurize each silo with nitrogen. As this is taking place, the Alaska’s navigators download the sub’s precise location to the missiles’ guidance computers. “You can’t hit anything unless the missiles know exactly where they’re starting from,” explains Weapons Officer Robert Farmer. Not by accident are 26 of the 160 men aboard navigators.

Next, three two-man teams of officers insert their unique keys to activate the launch trigger – a black-plastic pistol-like handgrip with a three-foot cord. If, at this bleak moment, someone in the room disputes the launch, he’ll be “Rodney King’d” by crewmen wielding low-tech wooden nightsticks – arrayed conveniently on the wall next to the door – and by at least one officer brandishing a sidearm. “Despite what you’d think,” says Farmer, “it’s okay to fire a pistol inside a sub. All it can hurt is us.”

As each missile is launched, its rocket motor vaporizes 55 gallons of water resting beneath it, and the weapon leaps out of its silo “in a blink,” says Farmer.

The recoil is colossal: “I once saw the whole second deck warp,” recalls an engineer. “Scared the crap out of me.”

It is not necessary that the crew know the missiles’ targets, “but we’re told none are aimed at population centers,” assures Farmer. “Just at hardware: sub pens, military bases, weapons-storage sites. And they’re real accurate. From 4000 miles, I can lob one into a baseball diamond” – something to keep in mind during next year’s World Series.

Farmer allows me to assist during a simulated “EAM missile spin-up.” “Wait for this yellow light to glow,” he instructs, “then squeeze the trigger and hold it until the light turns green – about three seconds.” I glare at the flickering lights as if staging an NHRA Funny Car, but I release the button too soon. Photographer Lorentzen grabs the trigger – “Let me show you how, hoss” he grumbles – although he, too, suffers identical finger flaccidity.

Ever ridden aboard a cruise ship? If so, a U.S. submarine has likely tracked your progress.

“What’re you two guys,” Farmer asks, “liberal-arts majors or something?”

We surface at dawn, then climb some 50 feet to the glistening bridge to watch SSBN 732 glide noiselessly, like a huge black eel, back into San Diego harbor. Up there, I am reminded that, apart from the space shuttle, a boomer is likely the most complex piece of machinery ever fashioned by mankind. A smiling 20-year-old planesman asks if I’ve ever driven a Lamborghini.

“Twice, I think,” I tell him.

“That is just so cool,” he coos, without averting his binoculars from a cargo ship on the horizon. “You got the world’s best job.”

“What about you?” I counter. “You live aboard a mechanical marvel that makes a Diablo look like a one-speed Schwinn.”

“Well . . . I guess,” he assents. “You know, right now I can’t legally rent a car or buy beer. Still, they sometimes let me drive a $1.8 billion submarine.”