To Be or Not to Be: Analyzing Hamlet’s Soliloquy

“To be, or not to be, that is the question.”

It’s a line we’ve all heard at some point (and very likely quoted as a joke), but do you know where it comes from and the meaning behind the words? “To be or not to be” is actually the first line of a famous soliloquy from William Shakespeare’s play Hamlet.

In this comprehensive guide, we give you the full text of the Hamlet “To be or not to be” soliloquy and discuss everything there is to know about it, from what kinds of themes and literary devices it has to its cultural impact on society today.

Full Text: “To Be, or Not to Be, That Is the Question”

The famous “To be or not to be” soliloquy comes from William Shakespeare’s play Hamlet (written around 1601) and is spoken by the titular Prince Hamlet in Act 3, Scene 1. It is 35 lines long.

Here is the full text:

To be, or not to be, that is the question,

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them? To die: to sleep;

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to, ’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wish’d. To die, to sleep;

To sleep: perchance to dream: ay, there’s the rub;

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause: there’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life;

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

The oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of despised love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office and the spurns

That patient merit of the unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscover’d country from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all;

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pith and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action.—Soft you now!

The fair Ophelia! Nymph, in thy orisons

Be all my sins remember’d.

You can also view a contemporary English translation of the speech here.

“To Be or Not to Be”: Meaning and Analysis

The “To be or not to be” soliloquy appears in Act 3, Scene 1 of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. In this scene, often called the “nunnery scene,” Prince Hamlet thinks about life, death, and suicide. Specifically, he wonders whether it might be preferable to commit suicide to end one’s suffering and to leave behind the pain and agony associated with living.

Though he believes he is alone when he speaks, King Claudius (his uncle) and Polonius (the king’s councilor) are both in hiding, eavesdropping.

The first line and the most famous of the soliloquy raises the overarching question of the speech: “To be, or not to be,” that is, “To live, or to die.”

Interestingly, Hamlet poses this as a question for all of humanity rather than for only himself. He begins by asking whether it is better to passively put up with life’s pains (“the slings and arrows”) or actively end it via suicide (“take arms against a sea of troubles, / And by opposing end them?”).

Hamlet initially argues that death would indeed be preferable: he compares the act of dying to a peaceful sleep: “And by a sleep to say we end / The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks / That flesh is heir to.”

However, he quickly changes his tune when he considers that nobody knows for sure what happens after death, namely whether there is an afterlife and whether this afterlife might be even worse than life. This realization is what ultimately gives Hamlet (and others, he reasons) “pause” when it comes to taking action (i.e., committing suicide).

In this sense, humans are so fearful of what comes after death and the possibility that it might be more miserable than life that they (including Hamlet) are rendered immobile.

Inspiration Behind Hamlet and “To Be or Not to Be”

Shakespeare wrote more than three dozen plays in his lifetime, including what is perhaps his most iconic, Hamlet. But where did the inspiration for this tragic, vengeful, melancholy play come from? Although nothing has been verified, rumors abound.

Some claim that the character of Hamlet was named after Shakespeare’s only son Hamnet, who died at age 11 only five years prior to his writing of Hamlet in 1601. If that’s the case, the “To be or not to be” soliloquy, which explores themes of death and the afterlife, seems highly relevant to what was more than likely Shakespeare’s own mournful frame of mind at the time.

Others believe Shakespeare was inspired to explore graver, darker themes in his works due to the passing of his own father in 1601, the same year he wrote Hamlet. This theory seems possible, considering that many of the plays Shakespeare wrote after Hamlet, such as Macbeth and Othello, adopted similarly dark themes.

Finally, some have suggested that Shakespeare was inspired to write Hamlet by the tensions that cropped up during the English Reformation, which raised questions as to whether the Catholics or Protestants held more “legitimate” beliefs (interestingly, Shakespeare intertwines both religions in the play).

These are the three central theories surrounding Shakespeare’s creation of Hamlet. While we can’t know for sure which, if any, are correct, evidently there are many possibilities—and just as likely many inspirations that led to his writing this remarkable play.

3 Critical Themes in “To Be or Not to Be”

There are many critical themes and questions contained in Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy. Here are three of the most important ones:

- Doubt and uncertainty

- Life and death

- Madness

There are many critical themes and questions contained in Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy. Here are three of the most important ones:

Theme 1: Doubt and Uncertainty

Doubt and uncertainty play a huge role in Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy. By this point in the play, we know that Hamlet has struggled to decide whether he should kill Claudius and avenge his father’s death.

Questions Hamlet asks both before and during this soliloquy are as follows:

- Was it really the ghost of his father he heard and saw?

- Was his father actually poisoned by Claudius?

- Should he kill Claudius?

- Should he kill himself?

- What are the consequences of killing Claudius? Of not killing him?

There are no clear answers to any of these questions, and he knows this. Hamlet is struck by indecisiveness, leading him to straddle the line between action and inaction.

It is this general feeling of doubt that also plagues his fears of the afterlife, which Hamlet speaks on at length in his “To be or not to be” soliloquy. The uncertainty of what comes after death is, to him, the main reason most people do not commit suicide; it’s also the reason Hamlet himself hesitates to kill himself and is inexplicably frozen in place.

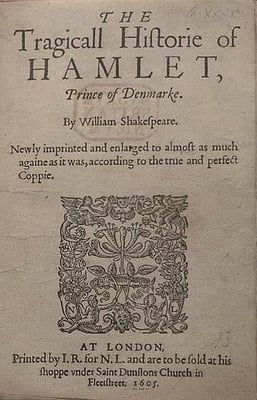

1789 depiction of Horatio, Hamlet, and the ghost

1789 depiction of Horatio, Hamlet, and the ghost

Theme 2: Life and Death

As the opening line tells us, “To be or not to be” revolves around complex notions of life and death (and the afterlife).

Up until this point in the play, Hamlet has continued to debate with himself whether he should kill Claudius to avenge his father. He also wonders whether it might be preferable to kill himself—this would allow him to escape his own “sea of troubles” and the “slings and arrows” of life.

But like so many others, Hamlet fears the uncertainty dying brings and is tormented by the possibility of ending up in Hell—a place even more miserable than life. He is heavily plagued by this realization that the only way to find out if death is better than life is to go ahead and end it, a permanent decision one cannot take back.

Despite Hamlet’s attempts to logically understand the world and death, there are some things he will simply never know until he himself dies, further fueling his ambivalence.

Theme 3: Madness

The entirety of Hamlet can be said to revolve around the theme of madness and whether Hamlet has been feigning madness or has truly gone mad (or both). Though the idea of madness doesn’t necessarily come to the forefront of “To be or not to be,” it still plays a crucial role in how Hamlet behaves in this scene.

Before Hamlet begins his soliloquy, Claudius and Polonius are revealed to be hiding in an attempt to eavesdrop on Hamlet (and later Ophelia when she enters the scene). Now, what the audience doesn’t know is whether Hamlet knows he is being listened to.

If he is unaware, as most might assume he is, then we could view his “To be or not to be” soliloquy as the simple musings of a highly stressed-out, possibly “mad” man, who has no idea what to think anymore when it comes to life, death, and religion as a whole.

However, if we believe that Hamlet is aware he’s being spied on, the soliloquy takes on an entirely new meaning: Hamlet could actually be feigning madness as he bemoans the burdens of life in an effort to perplex Claudius and Polonius and/or make them believe he is overwhelmed with grief for his recently deceased father.

Whatever the case, it’s clear that Hamlet is an intelligent man who is attempting to grapple with a difficult decision. Whether or not he is truly “mad” here or later in the play is up to you to decide!

4 Key Literary Devices in “To Be or Not to Be”

In the “To be or not to be” soliloquy, Shakespeare has Hamlet use a wide array of literary devices to bring more power, imagination, and emotion to the speech. Here, we look at some of the key devices used, how they’re being used, and what kinds of effects they have on the text.

#1: Metaphor

Shakespeare uses several metaphors in “To be or not to be,” making it by far the most prominent literary device in the soliloquy. A metaphor is when a thing, person, place, or idea is compared to something else in non-literal terms, usually to create a poetic or rhetorical effect.

One of the first metaphors is in the line “to take arms against a sea of troubles,” wherein this “sea of troubles” represents the agony of life, specifically Hamlet’s own struggles with life and death and his ambivalence toward seeking revenge. Hamlet’s “troubles” are so numerous and seemingly unending that they remind him of a vast body of water.

Another metaphor that comes later on in the soliloquy is this one: “The undiscover’d country from whose bourn / No traveller returns.” Here, Hamlet is comparing the afterlife, or what happens after death, to an “undiscovered country” from which nobody comes back (meaning you can’t be resurrected once you’ve died).

This metaphor brings clarity to the fact that death truly is permanent and that nobody knows what, if anything, comes after life.

#2: Metonymy

A metonym is when an idea or thing is substituted with a related idea or thing (i.e., something that closely resembles the original idea). In “To be or not to be,” Shakespeare uses the notion of sleep as a substitute for death when Hamlet says, “To die, to sleep.”

Why isn’t this line just a regular metaphor? Because the act of sleeping looks very much like death. Think about it: we often describe death as an “eternal sleep” or “eternal slumber,” right? Since the two concepts are closely related, this line is a metonym instead of a plain metaphor.

#3: Repetition

The phrase “to die, to sleep” is an example of repetition, as it appears once in line 5 and once in line 9. Hearing this phrase twice emphasizes that Hamlet is really (albeit futilely) attempting to logically define death by comparing it to what we all superficially know it to be: a never-ending sleep.

This literary device also paves the way for Hamlet’s turn in his soliloquy, when he realizes that it’s actually better to compare death to dreaming because we don’t know what kind of afterlife (if any) there is.

#4: Anadiplosis

A far less common literary device, anadiplosis is when a word or phrase that comes at the end of a clause is repeated at the very beginning of the next clause.

In “To be or not to be,” Hamlet uses this device when he proclaims, “To die, to sleep; / To sleep: perchance to dream.” Here, the phrase “to sleep” comes at the end of one clause and at the start of the next clause.

The anadiplosis gives us a clear sense of connection between these two sentences. We know exactly what’s on Hamlet’s mind and how important this idea of “sleep” as “death” is in his speech and in his own analysis of what dying entails.

The Cultural Impact of “To Be or Not to Be”

The “To be or not to be” soliloquy in Shakespeare’s Hamlet is one of the most famous passages in English literature, and its opening line, “To be, or not to be, that is the question,” is one of the most quoted lines in modern English.

Many who’ve never even read Hamlet (even though it’s said to be one of the greatest Shakespeare plays) know about “To be or not to be.” This is mainly due to the fact that the iconic line is so often quoted in other works of art and literature—even pop culture.

And it’s not just quoted, either; some people use it ironically or sarcastically.

For example, this Calvin and Hobbes comic from 1994 depicts a humorous use of the “To be or not to be” soliloquy by poking fun at its dreary, melodramatic nature.

Many movies and TV shows have references to “To be or not to be,” too. In an episode of Sesame Street, famed British actor Patrick Stewart does a parodic version of the soliloquy (“B, or not a B”) to teach kids the letter “B”:

There’s also the 1942 movie (and its 1983 remake) To Be or Not to Be, a war comedy that makes several allusions to Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Here’s the trailer for the 1983 version:

Finally, here’s one AP English student’s original song version of “To be or not to be”:

As you can see, over the more than four centuries since Hamlet first premiered, the “To be or not to be” soliloquy has truly made a name for itself and continues to play a big role in society.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Hamlet’s “To Be or Not to Be”

William Shakespeare’s Hamlet is one of the most popular, well-known plays in the world. Its iconic “To be or not to be” soliloquy, spoken by the titular Hamlet in Scene 3, Act 1, has been analyzed for centuries and continues to intrigue scholars, students, and general readers alike.

The soliloquy is essentially all about life and death: “To be or not to be” means “To live or not to live” (or “To live or to die”). Hamlet discusses how painful and miserable human life is, and how death (specifically suicide) would be preferable, would it not be for the fearful uncertainty of what comes after death.

The soliloquy contains three main themes:

- Doubt and uncertainty

- Life and death

- Madness

It also uses four unique literary devices:

- Metaphor

- Metonymy

- Repetition

- Anadiplosis

Even today, we can see evidence of the cultural impact of “To be or not to be,” with its numerous references in movies, TV shows, music, books, and art. It truly has a life of its own!

What’s Next?

In order to analyze other texts or even other parts of Hamlet effectively, you’ll need to be familiar with common poetic devices, literary devices, and literary elements.

What is iambic pentameter? Shakespeare often used it in his plays—including Hamlet. Learn all about this type of poetic rhythm here.

Need help understanding other famous works of literature? Then check out our expert guides to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, and quotations in Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird.

Need more help with this topic? Check out Tutorbase!

Our vetted tutor database includes a range of experienced educators who can help you polish an essay for English or explain how derivatives work for Calculus. You can use dozens of filters and search criteria to find the perfect person for your needs.