The Last Days of Sting

Steve Borden’s last match for World Championship Wrestling is scripted to look like a celebration.

It is March 26, 2001, and the country’s second-largest wrestling promotion is airing the final broadcast of Monday Nitro, its flagship show on TNT, live from Panama City, Florida. WCW, plagued by bad creative decisions and deepening financial losses, is finished, the loser of a bitter, five-and-a-half-year ratings war with the rival World Wrestling Federation. Three days earlier, WWF chairman Vince McMahon bought its assets; this last broadcast starts on a pre-taped segment of McMahon gloating that the fate of WCW is in his hands, real-life boardroom drama bleeding over into a scripted medium like it had so many times over the last half-decade. He’ll appear again on the closing segment, too, rubbing salt into the mortal wound of his only true competitor.

But before that, there is still room for one more match. There is still room for Borden to transform into Sting, WCW’s greatest star, one more time.

Borden hasn’t wrestled in months, but as he assures the television audience in his pre-match promo, he would not miss this. He could not. Hundreds of other wrestlers have come and gone since WCW’s inception, in 1988, and a couple dozen carried the company as headliners in the generation that elevated pro wrestling to a national phenomenon. But none of them mattered more than Borden—“The Franchise,” as the company dubbed him years earlier.

The opening riff of Metallica’s “Seek & Destroy” blares, and he marches to the ring in his customary attire. Black trench coat. Black gloves. Black boots. A long black singlet with white scorpions emblazoned on the sides. All of it works in service to his white-and-black painted face, the most striking visage in wrestling. The WCW announcer crew reminds viewers what Borden has meant to the company. How, from the very beginning, Sting was a standard bearer. Its world champion many times over. Most of all, as it hemorrhaged talent, that he stayed until the very end.

“This man proved, night after night, what loyalty meant,” color commentator Scott Hudson says, just after Borden sheds the trench coat to reveal his former bodybuilder’s physique, all brawny arms and bulging traps.

Already in the ring is Borden’s opponent, his longtime rival, “The Nature Boy” Ric Flair. They’ve worked together hundreds of times, sometimes in grueling matches stretching 45 minutes or more, like their transcendent time-limit draw from 13 years earlier that put Sting on the map. Tonight, they’ve got seven minutes. Flair, fresh off his 52nd birthday, wears a black Monday Nitro T-shirt over his trunks to hide his midsection. If this is to be their last dance, as Bordon claimed in his promo, they, too, deserve a better ending.

None of that matters once the bell rings, because Borden is electric. He traded on physicality well before he learned to work an audience with theatrics, and all these years later, after months out of action, there’s an ease to his movements. He is imposing but not lumbering, explosive yet controlled. He throws right hands and inside-out forearms and boots to the gut. He springs into the air for a two-footed kick, a condor floating like a hummingbird. He hoists Flair’s 240 pounds high above his head, arms fully extended, then slams him onto his back. He ascends the ring ropes, grabs Flair on the top turnbuckle, and flings their bodies backward so they crash onto the mat in unison. The crowd eats up every bit of it. Sting-er! Sting-er! Sting-er!

They know the finish when they see it: Sting bending Flair into a pretzel for his Scorpion Death Lock submission. A crescendo rips through the arena as Flair feverishly nods for the match to stop, and the referee raises Sting’s arm in victory.

Then Borden breaks away to pull Flair to his feet, wrapping his left arm around his old adversary’s neck for an embrace. After that, a handshake. The audience is enraptured. “Thank you, Steve Borden,” Hudson says to viewers, before launching into a monologue about what Sting and Flair have meant to professional wrestling.

The occasion is hardly perfect, but the moment is the best send-off possible—for WCW and perhaps for Borden, too. He turned 42 two days earlier, not old in wrestling terms but hardly young. No one, him least of all, ever pegged him for a lifer, and now he doesn’t need to be. He has a wife and three kids at home. He’d already become a millionaire several times over, and he’s due millions more on the balance of his contract.

What better time to walk away? What better way for Sting to disappear?

✰✰✰

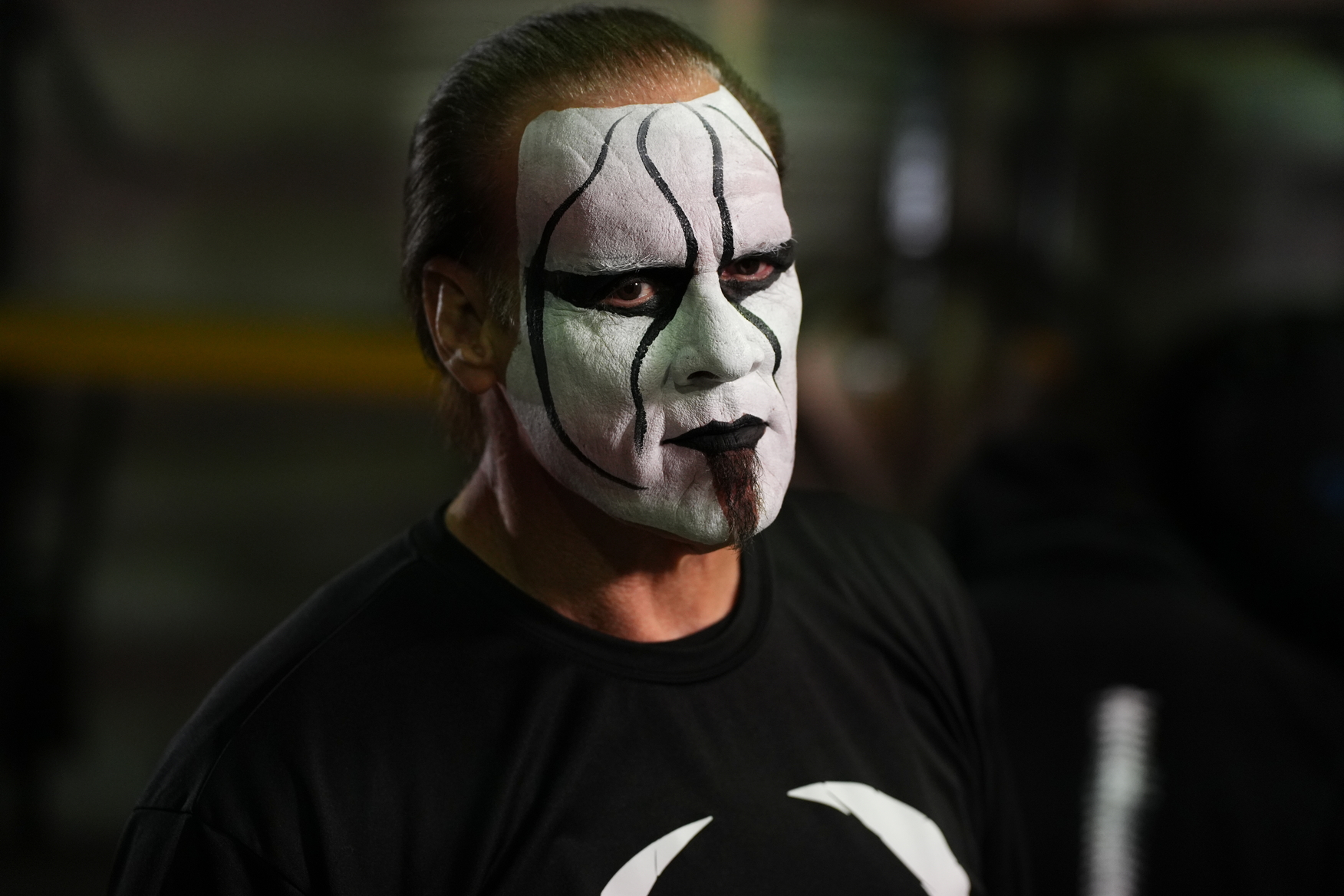

Twenty-two years later, at age 63, Borden is still putting on his makeup.

First comes the layer of white theater paint, from the tip of his hairline to his chin, taking care to navigate around the strip of facial hair that juts below his lower lip. Then, the black. A coat across his lips. Two rings around his eyes. Four curved lines to frame them. Age has taken its toll on other elements of his appearance since that night two decades ago. Borden’s hair is thinner; he slicks it back to cover his scalp. He, too, now wears a black T-shirt over his singlet. But once the paint goes on, he remains one of the most captivating performers in wrestling.

Back in the WCW days, the whole process took as little as 10 minutes. Now it requires about 20. Everything takes longer now. On nights when he’s on the card for All Elite Wrestling, his employer since 2020 and the eventual heir to WCW as the country’s second-largest promotion, he needs an hour of warmup in his dressing room to prepare his body for the pounding it takes. (The World Wrestling Federation, the biggest promotion, rebranded as World Wrestling Entertainment in 2002 after a trademark dispute with a nonprofit that shared its initialism, the World Wildlife Fund.) Usually, that warmup includes a visit from the company’s physical therapist to align his hips and tend to one of his several problem areas: his left elbow, his right shoulder, and his knees, the latter of which gave him the most trouble before he had surgery to clean out bone spurs in October. That’s without considering his neck, a public source of scrutiny after he was diagnosed with spinal stenosis following an in-ring accident in 2015, the event everyone—including him, for a while—presumed would end his in-ring career. Recovery times are unpredictable. So are his workouts.

“It’s like a potluck, picking and choosing on a daily basis what I’m able to do,” Borden says by phone. He’s among the lucky ones. “I have all the original body parts,” he says. Most of his contemporaries can’t say the same, nor can wrestlers in the generation after them. Whenever he runs into one of them at a convention or a signing, he’s come to expect the other man to shuffle around on a cane or a replaced joint.

Over the years, he watched them climb out of the ring, one by one, the way he never could. Some left by choice; more by circumstance. Too few exited when they should have. Pro wrestling is a business of lifers, a carnival of entertainers addicted to the attention of a live crowd, physical performance, backstage camaraderie, and freedom from a 9-to-5.

“You can’t get that excitement in real life that you can get in wrestling,” says Dave Meltzer, who has covered the sport since 1971 for his Wrestling Observer Newsletter.

Nor can most of them get the money, from the seven-figure salaries earned by national television headliners down to the scraps for those drawing off faded glory in gyms or assembly halls on the independent circuit.

Borden has outlasted all of them, which wasn’t his intention. “I swore to myself, ‘I’m never going to be one of those guys,’” he says, “and I’m one of those guys 10 times over.”

His 17-acre ranch in Waxahachie beckons with distractions for a man who enjoys working the land (he owns a tractor and is in the market for a skid steer) and who is so guarded about it that Nikita Koloff, one of his oldest friends in wrestling, jokes, “It’s Fort Knox to get into that place.” His legacy is established. Few performers are more beloved within the industry, as much for his accomplishments—15 world championships, hundreds of headlining matches, nearly 40 years of quality work—as for the relatively understated way he did his job. Hence AEW’s ring announcer often introducing him as “The Legend,” “The Icon,” on his walk to the ring.

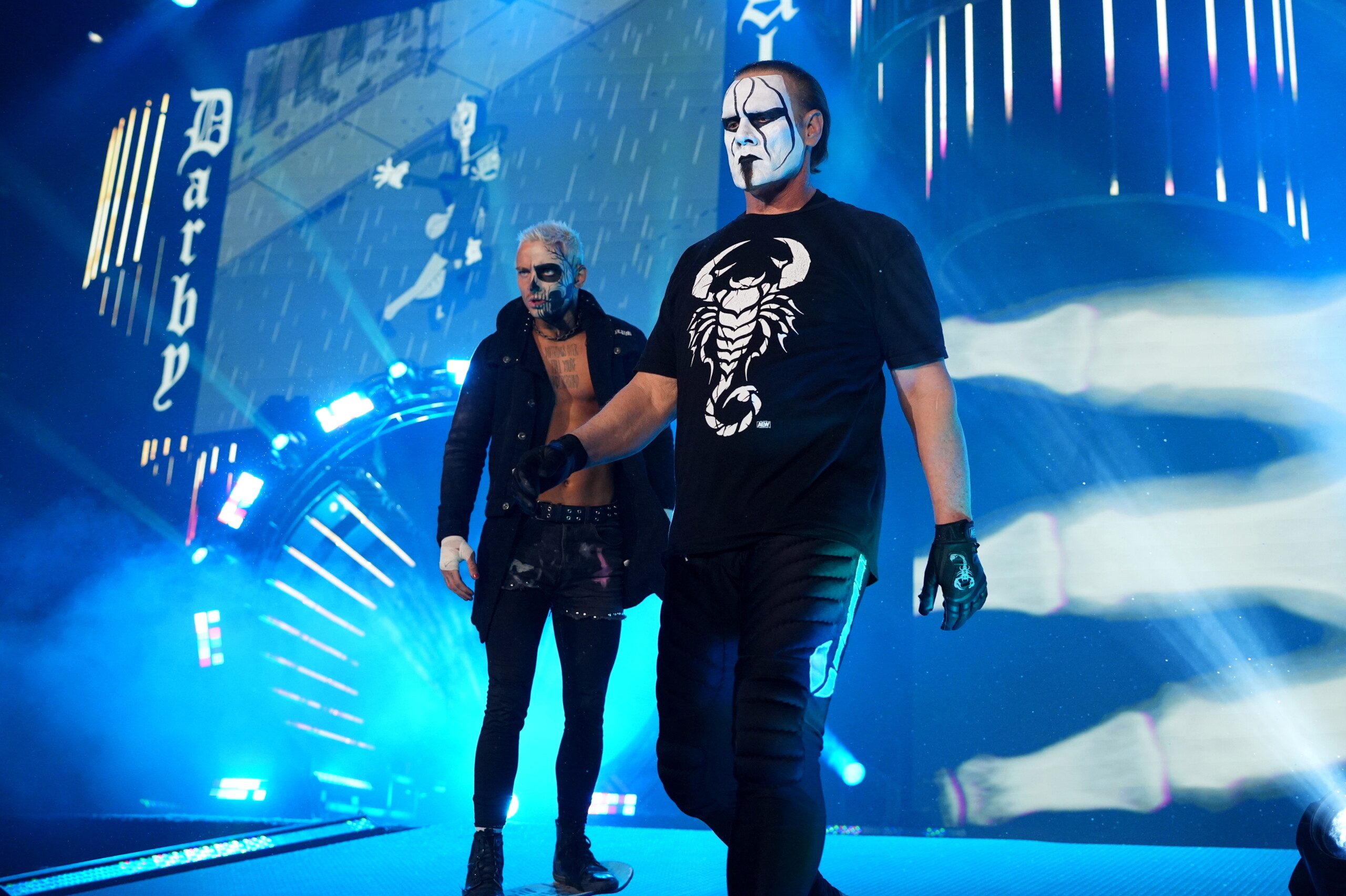

“He transcends pro wrestling. He’s like pop culture,” says Darby Allin, his tag team partner. “You may not know any of the stuff he’s done, but you can see the face paint, and people will go, ‘Yo, that’s that wrestler guy.’”

Even now, two years into his time on the roster of AEW, his latest and last employer, he occasionally assures shy wrestlers that it’s OK to approach him. “For a lot of these guys, it’s like Elvis walking in the door,” says Arn Anderson, who has known Borden since they first wrestled in the same territory in the ’80s and who now works for AEW as a coach.

Still, Borden won’t allow himself to rest. Not yet. He is chasing the one thing that keeps eluding him in his wrestling twilight: a final act. The right performance to cap off a storied career. A moment, a storyline—something—constructed with his bosses at AEW to bring him fulfillment. And until he attains it, he’ll keep pushing himself further than any wrestler his age ever has. There is no corollary for someone so accomplished performing regularly on national television this late in life.

Even now, Borden walks to the ring as one of pro wrestling’s most revered performers. Photo courtesy of All Elite Wrestling.

“To be in our profession and operate at the very highest level—to even get that, let alone maintain it for over three decades, is mind-boggling,” says Lex Luger, his closest friend in wrestling and former business partner.

As a result, says Meltzer, the longtime wrestling journalist, “he could basically go in there and throw a few punches and do 40 seconds worth of work, and he’s Sting, and it would be OK.”

Instead, ever since Borden returned to the ring in March 2021, following a five-and-a-half-year hiatus, he has upped the ante, continually testing the limits of what his sexagenarian body can take. Intellectually, he embraces the concessions he must make to age: a lower spot in the company hierarchy, the end of energy-sapping one-on-one contests. That doesn’t help him sleep better on the nights after he wrestles, when he replays sequences in his mind and pries at the weak points in his performance.

His wife worries. So do some of his friends. But they’re also curious. They, too, wonder how Sting’s story ends. “It’s like, How many Super Bowls do I need to win?” Koloff says. “When is enough, enough?”

Borden knows only that it’s soon. His deal with AEW expires sometime this year; he won’t say exactly when. When it ends, so will his time behind the face paint.

✰✰✰

He was 27 years old the first time he put on the paint: black lips and a football player’s eye black. Rudimentary, like everything else about him at the time.

It was 1986, and Borden was less than a year into a life he never knew he wanted. He’d spent the better part of his 20s drifting around Southern California. Bodybuilding, bouncing, bartending, gym management: all the stereotypical vocations a washed-up junior college basketball player—“a 6-foot-2 White guy going nowhere,” he says—would wander into.

He didn’t even know what pro wrestling was. He has told the story before: manning the desk at a Gold’s Gym in Reseda, a suburb of Los Angeles in the San Fernando Valley, wondering about “the big guy with blond hair” whom everyone clamored over whenever he came to work out. Hulk Hogan, he was told, not that the name registered; he could place the most famous wrestler on the planet only as “the guy from the Rocky movie.” Maybe that’s all Hogan ever would have been to him had not a consultant named Rick Bassman strolled in one day, looking to assemble a team of four Gold’s Gym bodybuilders to train up and, the hope went, eventually get signed by WWF, then just a territorial wrestling company out of New York. After a few weeks, Bassman had one spot left to fill. “What about you?” he asked Borden. Once Bassman brought him to a WWF show in Los Angeles, Borden began wondering the same thing. Peering down at the spectacle in the ring, blanketed by the roar of thousands around him, it all clicked.

Three months later, Borden piled into his 1983 blue Thunderbird and sped toward Memphis, Tennessee. Riding shotgun was his new tag team partner, Jim Hellwig, a colossal Indiana native who had been studying to be a chiropractor. Their destination was the Continental Wrestling Association, one of roughly 30 regional territories that comprised the American pro wrestling scene. For the next year, Borden and Hellwig bounced around the Southeast, first under the names Flash and Justice in a group called Powerteam USA before moving to a Louisiana territory called the Universal Wrestling Federation and getting repackaged as Sting and Rock—the Blade Runners.

All the while, Borden had one goal in mind. “I looked at all these guys a generation before me, and I thought, ‘Man, why do they stay in it so long?’” he says. “I don’t get it. Make your money, do what you want to do, and get out.”

The Blade Runners were ascending, slowly, but they were also broke. A good day’s work paid $25. Most days, it was less. They’d sleep in the T-Bird and sometimes eat only inside grocery stores by stealing a rotisserie chicken from the deli counter and taking turns sneaking bites as they pushed their cart along the aisles.

Midway through 1986, Hellwig left to go it alone. He’d become The Ultimate Warrior, a future WWF champion and ’80s icon, the other half of the two most successful solo acts ever to bloom from the same tag team.

Borden, as Sting, would become even bigger. By then, professional wrestling was changing. McMahon bought WWF from his father, Vincent, with designs on scaling it up to a national operation. One by one, he gobbled up smaller companies. A New York promotion became a Northeastern one, then a national outfit. Not to be outdone, another son of a wrestling promoter, Charlotte-based Jim Crockett Jr., started consolidating Southern territories under the arm of Jim Crockett Promotions. A duopoly took shape, with each side needing new stars to combat the other.

Crockett’s star was Borden, who by 1988 had come into his own. He took his Blade Runner aesthetic— face paint, a bleached-blond flat top, and his muscle-bound body—and pushed it further, bolder. The basic black paint evolved into medallions of every hue, accompanied by a similarly flamboyant ring jacket and tights. Reserved outside of the ring, Borden fashioned a Sting persona that took him in the other direction. He’d whip the crowd into a frenzy by pounding his chest or cup his hands to his mouth, tilt his head back, and howl to them, whereupon they’d howl back. In matches, he’d launch himself over the top rope and off the ring’s highest turnbuckle, the sort of stunts no one close to his size would try. Set against a world of basic trunks and even more basic wrestling maneuvers, it was jarring. When he executed the Stinger Splash, a running leap from the middle of the ring onto his opponent standing in the corner, he felt like the future personified.

“To be in our profession and operate at the very highest level—to even get that, let alone maintain it for over three decades, is mind-boggling.”

Lex Luger

“Like that poster of Michael Jordan doing the dunk from the free-throw line,” says Christopher Daniels, AEW’s manager of talent relations, who has shared a promotion with Borden for parts of the last 20 years.

Borden and Flair wrestled their epic 45-minute draw the same year, and the future became the present. For the next decade, Sting reigned as one of pro wrestling’s biggest attractions in what would become WCW. He could have ridden that wave for decades to come, pandering to crowds in fluorescent outfits and slapping hands with fans every time he bounded down to the ring. Instead, at the peak of his powers, in 1996, Borden reinvented himself. Out went the hair dye, the flat top, the flashy outfits. In their stead came his black-and-white current aesthetic, popularly known as “The Crow” for its resemblance to Brandon Lee’s protagonist in the 1994 action flick of the same name—although Borden says the inspiration also came from KISS, Marilyn Manson, and The Rocky Horror Picture Show. This new Sting was laconic and mysterious. He was a dogged champion for justice. If Borden’s old character was a departure from his true self, this one was an extension of it.

“He’s not playing make believe,” says Jeff Jarrett, AEW’s director of business development, who has known Borden since the ’80s. “There’s a component of Steve’s personality that is Sting.”

Borden clutched a baseball bat and brooded on arena catwalks, sometimes rappelling from the ceiling to wreak havoc. He went a calendar year without saying a word on camera or wrestling a match, a gambit that hadn’t been attempted before or since by a performer of his caliber. That restraint only made his star burn hotter right as pro wrestling was reaching its zenith in America. The television audience ballooned, with both WCW and WWF scoring ratings that had rarely been seen in pro wrestling and haven’t been topped since flagship shows ran head-to-head in what became known as Monday Night Wars. One prominent WCW match of the era included Dennis Rodman and Karl Malone wrestling each other weeks after the Chicago Bulls and Utah Jazz had squared off in the NBA Finals. Another featured Jay Leno, at the height of his Tonight Show run, working a tag-team contest against Hulk Hogan. WWF countered by bringing in Mike Tyson less than a year after he’d bitten off a portion of Evander Holyfield’s ear in a heavyweight boxing match. Cable audiences couldn’t get enough, routinely watching in numbers that topped Major League Baseball and college football audiences.

In 1997, no one was bigger than Sting. A decade removed from sleeping in his car, Borden was making seven-figure money; he says he was told that he generated more than half of the company’s merchandise sales. His return to the ring in December of that year—against Hogan, of all people—recorded the second-highest pay-per-view buyrate (the percentage of households with access to an event that purchased it) in wrestling history at the time and eclipsed Holyfield’s heavyweight championship boxing match one month earlier. More than ever, he was WCW’s standard bearer. How could anyone but him win that final match in Panama City?

The journey might have ended there. Pro wrestling, his accidental life’s work, had enriched his life more than he’d imagined possible, and he’d escaped its seedy undertow, swearing off steroids around 1990, before shaking booze, pills, and womanizing when he became a born-again Christian in 1998. He’d preserved his fortune, too, funneling much of it into real estate, an interest of his since the ’80s that grew into a passion once he’d amassed a bankroll and gotten savvy to investment strategies. “He could have quit any time if it were about the money,” says Anderson.

Borden never imagined he’d be wrestling into his 60s. Photo courtesy of All Elite Wrestling.

Which, for a while, he did. From 2001 through 2005, Borden barely stepped foot in the ring. Unlike many of his coworkers, he turned down overtures from McMahon and WWE to come aboard after he’d bought WCW’s assets, instead contenting himself with the occasional overseas tour and a limited-appearance deal with an upstart called Total Nonstop Action (TNA). He stayed home with his family, dabbling in real estate and ministry, even starring in a Christian-themed biopic, Sting: Moment of Truth. He had made his money, done what he’d wanted to do, and gotten out.

Except, by 2006, he wasn’t so sure. Wrestling tugged at him. Yes, he’d gotten out, but real or imagined, he says he felt pressure to continue providing for his family. More than that, had he really done all he’d wanted to do? He may have won that final WCW match, but his last moment on a national stage came as the company he helped build—his company—went under.

“I just didn’t want [to leave] with my tail between my legs after the years of sacrifice and everything else,” he says. Before the year was out, he came to an agreement with TNA on a full-time contract where, at 46 years old, he reprised his role from WCW as the face of a fledgling company challenging the WWE empire.

The seasons of his life changed and kept changing. Forty-six became 50, then 55, then 60. He divorced and remarried; his kids grew up and moved out. He moved from Atlanta to Southern California, and from Southern California to North Texas. He switched employers twice more: first to WWE, then to AEW. In time, all that remained were two constants. He kept putting on the paint, white then black, top to bottom. And he kept searching for the right time, the right moment, to remove it for good.

✰✰✰

Technically, he’s already retired once: in 2016, when working for WWE. It irks him—another example of things not going according to plan.

“So many of the guys retire and then they come back, and I thought, ‘I’m not going to be like all the rest of the guys,’” he says. “Just like I said in the beginning, ‘I’m not going to be in this in 45 years.’

“And here I am.”

He’d counted on WWE being his last stop when he signed with the company two years earlier. Things had run their course in Total Nonstop Action, by then renamed Impact Wrestling. He had come to the company intent on elevating it to a national force and instead spent a dozen years riding out creative upheaval, ownership changes, financial constraints, and a revolving door of talent. “There came a time when you realized, ‘This is not gonna happen,’” he says. He began mulling his exit plans.

The obvious solution, the only answer, was WWE. Nowhere else could afford him. But, more than that, nowhere else would mean as much. He remained WWE’s white whale, the one marquee talent McMahon could never lure. So, once his contract expired, in January 2014, he sent a text to McMahon and McMahon’s son-in-law, Paul “Triple H” Levesque, a WWE vice president and semi-retired former world champion: “Have you turned the page on Sting yet?”

Borden had an idea. He didn’t covet another world championship run, nor to main event the company’s pay-per-views. What he wanted was a single match—in his mind, the match. He wanted Mark Calaway, better known as The Undertaker. Six years younger than Borden, Calaway was in many ways his counterpart, a WWE institution who, like Borden, portrayed a character as mysterious on-screen as the man playing it was off-screen. By then, Calaway’s body was so beaten up that he rarely wrestled more than once a year, every April at WrestleMania, the company’s signature show. But he was such an attraction that even selecting The Undertaker’s annual opponent had become dependable television fodder. And if his opponent were Sting? It would be the talk of the industry. Land that match, Borden figured, and he would finally be fulfilled. He envisioned a spectacle that featured not only wrestling but magicians, holograms, disappearing acts—a production befitting wrestling’s two most hallowed characters.

“Let’s have one, big, gigantic reuniting of The Beatles,” he says. “One time, and that’s it.”

McMahon replied to Borden’s text within minutes. A deal was done in a matter of weeks. Borden says he brought up the match only once, prior to signing his contract. He was told Calaway’s opponent was already booked for the spring, but he wasn’t deterred. He figured he’d sign the deal, then politic his way into a showdown with Calaway down the road. Millions of fans would want to see Sting take on The Undertaker.

In the meantime, McMahon delivered his WrestleMania assignment: his son-in-law, Levesque. It was a different sort of dream match but a dream match nonetheless, a first-time meeting between two of the most decorated champions in wrestling history in front of more than 75,000 people at Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, California. Then it happened. The 18-minute affair was disjointed and overproduced, with WCW and WWE wrestlers from the late ’90s popping in to run interference. The commentary team peppered the broadcast with references to the Monday Night Wars, calling Borden “the last soldier of WCW, the company that tried to put [the McMahon] family out of business.”

The finish came when Borden lined up a Stinger Splash, only for Levesque to run out of the corner and meet him head on. Levesque’s hands were cupped around the head of a sledgehammer; he jabbed it into Borden’s skull, and Sting collapsed to the mat like a running back leveled by a defensive lineman. Levesque theatrically dropped the hammer, then fell to his knees before crawling over to pin Borden’s shoulders.

After chasing him for two decades, McMahon had booked Sting to lose his debut. The crowd at Levi’s was tepid. Whatever cheers broke through the television broadcast were drowned out by Levesque’s theme music and a WWE commentator crowing that “the right side won again!” The whole scene came off a victory lap for McMahon, a man who had long ago conquered everything that mattered.

“Vince was still reliving the wrestling war,” Meltzer says, “and Sting would always be that representation of the wrestling war.”

Borden came to grips with his lot in WWE. He mattered, but not in the way he’d hoped for and never in the way he could. That match he coveted with The Undertaker? “It was never going to happen,” Borden says, before letting out a small, sad chuckle. “Never.” Everywhere else in wrestling, he was The Legend, The Icon, The Franchise. In WWE, he was a trophy.

“I just didn’t want [to leave] with my tail between my legs after the years of sacrifice and everything else.

Steve Borden

But he had a contract, and he kept wrestling until September 20, 2015, when he main evented a pay-per-view against the company’s 29-year-old champion, Seth Rollins. Everything was going to plan until Rollins called for the first of two buckle bombs, a maneuver in which he would hoist Borden’s legs over his shoulders and launch him back-first into the corner turnbuckle. It was a staple of Rollins’ arsenal, a move performed without incident a couple of hundred times a year.

That night, it went wrong. Borden landed on the base of his neck. Shock waves ran down both his arms. His fingertips tingled. He clenched and unclenched his fists, and shook his arms, trying to jolt feeling into his extremities.

He was still trying to right himself four minutes later, when it came time for a second buckle bomb. This time, weakness ran down to his legs. He wobbled out of the corner, clinging to the top rope for support. The next moments called for Borden to run across the ring, bouncing off the opposite set of ropes with a head of steam. All he could muster was an unsteady trot before crumpling to the ground.

After lying on the mat for a minute and a half, with the aid of the referee and a WWE doctor, Borden willed himself back to his feet long enough to work a finishing sequence and complete the match. He left the arena in an ambulance, and was handed a diagnosis by the next morning: spinal stenosis, a narrowing in the spinal cord that compresses nerves. WWE doctors recommended surgery.

Surely, this was it. How could it not be? Fifty-six-year-old financially secure men with wives and children do not climb into the ring with spine problems. He eventually opted against the surgery, citing advice he received from wrestling luminaries Stone Cold Steve Austin and Edge, who had undergone neck procedures. He says the swelling in his spinal column went away on its own, that he felt like himself six weeks after the injury.

Still, WWE would not clear him to wrestle. Borden’s wife, Sabine, hoped the Rollins match would be the long-awaited catalyst for retirement. Before long, he realized it’s what the company wanted, too. (WWE did not comment following a request from D Magazine.)

It was subtle at first: a phone call from Levesque announcing that the company wanted to induct him into its Hall of Fame at WrestleMania weekend in Dallas in April 2016. While Borden was flattered, he knew the score. Active wrestlers rarely get the nod. When he asked Levesque if the company wanted him to retire, the vice president assured him otherwise. As Borden recalls, “He says, ‘No, no, no, no. Uh-uh. No. This is not a retirement speech.’”

As the event approached, though, he could feel the winds shift. He is quick to note that he “wasn’t forced into it, [and] nobody made me do it.” But he does recall a conversation with McMahon, where the chairman told him that whenever were Borden to end his in-ring career, “I’d rather it be here under this umbrella. WWE.”

Borden could read between the lines. “I just felt like everything was”—he pauses to break into a sharp laugh—“pointing toward, ‘You just need to retire. Just get it over with.’ … I finally relented and said, ‘Alright. Let’s just do it.’”

So he stood onstage in the American Airlines Center in a tuxedo, without face paint, and told fans that his wrestling career was over. He did his best to project fulfillment, pride, but none of it felt right. When he uttered the words “retire tonight,” he made a small, seemingly unintentional frown. It never left his face as he pulled back from the podium to watch the audience stand in applause.

He realized what was happening. He’d created that perfect moment he’d been searching for, the fulfillment of a career. But it belonged to Vince McMahon.

✰✰✰

Four years after giving McMahon what he’d wanted, Borden appeared on AEW television for the first time. It felt less like a comeback than making things right. His new boss, AEW’s 40-year-old co-founder, president, and CEO Tony Khan, agrees. Khan is the son of Jacksonville Jaguars and Fulham FC owner Shad Khan; the younger Khan holds positions in both teams’ front offices. Ever since childhood, however, Tony Khan’s passion has been professional wrestling. It’s what led him to start AEW along with a trio of wrestlers in 2019, why he bought another wrestling company in 2021, and how he summons the energy to run creative for each enterprise while working two other jobs.

Like any wrestling obsessive who grew up in the late ’80s and early ’90s, Khan says, “I woke up to Sting.” That’s why, in Khan’s role with the Jaguars, he was tickled to chat with Borden in 2017 when he inquired about getting a Sting-signed bat for the team. “I liked the person so much, I forgot about the bat,” Khan says. Once he, like McMahon five years earlier, got a message from Borden expressing interest in wrestling again, Khan pounced.

Where McMahon saw the face of his competition, Khan sees “a real-life superhero” whose arrival has been transformational for AEW. The company treats him like the legend he is. Borden dresses in a private locker room, a perk he admits almost sheepishly and is adamant that he did not ask for. When it came time to begin training for his return, AEW shipped a ring to Waxahachie, which the company erected in an insulated barn on his ranch. He still works prime slots on the card, and for an on-screen accompaniment, they paired him with Allin, a 29-year-old daredevil who ranks among the brightest stars in the company.

Borden with Darby Allin, his on-screen tag team partner and off-screen friend. Photo courtesy of All Elite Wrestling.

That treatment could breed resentment in an outfit stuffed with far more talent than it can fit on television each week. But backstage Borden is revered. A wrestler nearly 40 years his junior once pulled him aside to show him a photo of himself dressed as Sting for Halloween. Several, Borden says, have turned to him for advice on how to live as a Christian in pro wrestling, wisdom he’s happy to dispense after he once served as a deacon at Fuego Church in Red Oak. When CM Punk, the company’s biggest mainstream star, teamed with Borden and Allin in a match in Greensboro, North Carolina, he wore special gear commemorating Borden’s draw with Flair in the same town 33 years earlier.

All of which explains why, when asked to describe Borden’s value to his company, Khan sounds like a sports executive who plucked a star player off another team’s bench. “He definitely had a lot more to offer than he’d be asked or allowed to show,” he says of what he saw in Borden’s WWE run. “To know that a wrestling company could have somebody like Sting—or really, specifically, Sting himself, because there’s nobody like Sting—under contract, and he would want to work, and they wouldn’t want to use him, it makes no sense to me. I don’t care what company it is, what time. I don’t care how many people you have under contract. If Sting wants to be active, and you have Sting on your roster, why wouldn’t you utilize him?”

Health, for one thing. But Khan is adamant: “Nothing in Steve’s medical history precluded him from coming back and wrestling. We did examine him and had no concerns.”

Maybe they weren’t worried, but they did start off cautiously. What began as a plan to do cinematic matches—pre-taped sequences instead of live ring work, often heavy on the special effects—evolved into a full comeback after just one match. Allin says he made that happen. After watching Borden close out the action in one take, Allin implored him, more or less, to remember who he is. Before long, Borden was back to wrestling regularly, sometimes every month. Each time, the crowd still jolts to life when he beats his chest. It still howls back when he cups his hands to his mouth.

Fans see what Allin saw, and what Khan saw before him. With everything Borden has accomplished since his return to television, the greatest is that he’s escaped becoming a nostalgia act. He can deliver most of his trademark maneuvers, and his physique has held up better, longer, than arguably anyone before him. The Stinger Splash recalls Jordan’s farewell tour with the Washington Wizards more than his soaring heyday with the Chicago Bulls, but it’s still credible. Sting still has it.

“No one’s looking at him and going, ‘Oh, well, that’s pretty good for a 63-year-old,’” says Daniels, the AEW talent relations manager. “They’re all saying, ‘Holy shit, look how cool this is. This is badass.’”

✰✰✰

Thirty years ago, Nikita Koloff succeeded where Steve Borden has so far failed. He made his money, did what he wanted to do, and got out.

Born Nelson Simpson, Koloff shot to prominence in the ’80s as one of pro wrestling’s premier bad guys, playing a Soviet-era villain with such gusto that he legally changed his name to that of his character’s. For the better part of a decade, he found himself across the ring from all manner of wrestling household names, Borden included. And when, in 1992, Koloff injured his neck during a match, he decided to quit while he was ahead. He was 33 years old, a baby by wrestling retiree standards. He’d be back, or so his colleagues figured.

But Koloff stayed out of the ring. He was born again the following year, and he lived his faith boldly. He proselytized whenever he ran into old friends in the business. Borden was one of his targets. It would take another half decade for Koloff’s message to sink in, but once it did, a deep friendship blossomed. The two attended conferences together, and, over a period of five years, Koloff estimates, he visited Borden’s ranch in Waxahachie once a quarter. There, they’d talk for hours—about God, about family, about life. Though the visits are less frequent these days, their chats continue over the phone.

Koloff remembers the call when Borden told him Khan’s offer to return to the ring. When he talks about it, he can’t help but recall his own exit. Koloff, too, was cleared to return to wrestle in 1992. Instead, he took a doctor’s warning to heart. One bad bump or fall could deal life-altering damage, and there is no promise of safety in a business where performers entrust their bodies to one another every night. Koloff was a young man when he reckoned with that knowledge. Borden is not now. “I’ll be praying for you,” Koloff told his friend.

Borden understands. He’s not, as he puts it, “a human super ball” in the ring anymore. He and Allin carefully script their matches to work around his limitations, and he isn’t afraid to tell an opponent he won’t take certain maneuvers. There’s a reason he still has all the original body parts. But he remains a pro wrestler, and as Daniels, who is still wrestling at age 52, says, to do the job is to “always want to see exactly where that edge is and peer right over it.”

Perhaps that’s why, about a year ago, Borden started leaping off things. The top turnbuckle. The AEW entrance tunnel. The ledge of an arena concourse. A guard rail, onto 7-foot-2 former Dallas Maverick Satnam Singh. Last March, at a pay-per-view event in Orlando, he climbed onto a balcony. A dozen feet below him, propped up on three tables, was Ric Flair’s 33-year-old son-in-law, Andrade El Idolo. Borden raised his left boot onto a guard rail amid a throng of shrieks, pausing to build tension before meeting it with his right. Then he belly flopped, plummeting downward until he crashed onto flesh and the wood snapped like graham crackers. It was almost harrowing to watch. The shrieks morphed into resounding chants of Holy shit.

And yet, Borden says, “I don’t know why, but I really don’t have a fear of it.” At an age when wrestling heroes hobble through convention hallways on replaced joints, Sting goes bigger than he ever has. It makes him seem indestructible.

All of his act does. Borden’s midsection may be a little softer, his hairline thinner, but the paint hides wrinkles while the black outfit covers up any sagging flesh. No wrestler is better equipped to maintain the illusion of time standing still when he steps through the ring ropes. It’s a powerful trick. It’s a dangerous one, too. The better the disguise, the easier it is to obscure what’s been lost through the years. The easier one can forget that the man flinging his body through the air has a spinal injury on his ledger and will soon be eligible for Social Security.

But Koloff hasn’t forgotten. “I 100 percent worry,” he says. “I would hate to see some sort of serious damage be done and then [he ends] up crippled for the rest of his life.”

Nevertheless, he and others in Borden’s orbit believe he’ll know the right moment to retire when he sees it. Unbeknownst to them, it nearly happened in September 2021 at Arthur Ashe Stadium in Queens, New York. At the time, it was Borden’s most ambitious match in AEW: a two-on-two affair against FTR, one of the world’s best tag teams, in which he carried much of the action. He clotheslined, body slammed, flew off the top rope. He beat his chest and launched into the Stinger Splash.

In his mind, none of it mattered. He’d tweaked his right hip in the days leading up to the match; that, in tandem with his balky knees, compromised his mobility. As the audience swooned over everything he could still do in his 60s, Borden fixated on what he couldn’t: the small, subtle movements his body refused to make. Imperceptible as they were to those watching, it was enough to drill one thought in his head: “Oh my gosh, I think this is it. We’ll have to figure out a creative way to make me bow out.”

“There were probably three different occasions during the match that I thought, ‘OK, this is embarrassing,’” he says. “I am thoroughly embarrassed. I will be reading online all these fans saying, ‘Yeah, it’s time for him to hang it up. Time caught up to him. He’s done.’”

They didn’t. And with each wave of positive feedback from his peers, he realized that there had been no need to slink past Khan backstage in fear that he’d let down his new employer. Still, he hasn’t forgotten the dread that surged through him. It’s why, as the end creeps closer, he hasn’t fixated too much on the particulars. He says Khan has broached the subject with him in conversation, while a number of wrestlers, some of whom Borden has never climbed in the ring with before, have put their names forward to be a part of it. No matter when it goes down, no matter who else is involved, it will be one of the most important moments in pro wrestling history.

Once a plan gets put into place, all of it becomes real. He’s finally ready for it emotionally. He certainly is physically. But there will be expectations. Hype. “And I’ve got some insecurities about that, I guess, mainly due to age,” he says. “The more focus, now you’ve got to follow that big build-up, you know?” He knows how it feels to be part of moments that fall flat. It happened in his WrestleMania debut, when McMahon scripted his defeat.

So while he’s sure that the details will get hashed out sooner than later, “Part of me, it’s like I want to avoid it,” he says. Because ultimately, the perfect exit isn’t about the timing or the opponent. It’s about the way he makes people feel—and the way he feels about himself.

“Whatever I do, I want wrestling fans to say, ‘That was incredible,’” he says. “I don’t want them to walk away going, ‘That was embarrassing.’ I just want it to be a great memory and then to just finally, once and for all, say, ‘Adios.’”

However he goes out, he’s excited about what awaits him next. Sabine, who grew up in Bavaria, Germany, has never known him outside of wrestling. His profession is the opening chapter of their marriage; they met shortly before his WWE run, when he needed someone to help him get back in ring shape. “There was only one trainer in this gym,” he says, wryly, “[and] she’s only got one client now.” She’s never seen much of the United States. So once he has the time, he wants to show her all the beauty he’s encountered in four decades of traveling the country. The Grand Canyon and Mount Rushmore. The Rockies and Lake Tahoe. Hidden gems accessed only by four-wheel drive. No schedule. No itinerary. “We stop when we want to stop,” he says. “We stay where we want to stay.”

Sometime soon, they’ll get started on that journey. But he has to finish the one in the ring first. He has a few more matches for Gracie, now 22 years old, to appreciate her father’s career in a way she never could as a child. He’s got a little while longer to work in the same company as his daughter-in-law, Katelyn, who is on AEW’s social media team and is training to be a wrestler. He can spend a bit more time mentoring Allin, who has transitioned from an on-screen partner to an off-screen friend.

They were back in the ring on November 19, six weeks after Borden’s knee surgery, for a match involving Jarrett, who brought him into TNA and whose father gave Borden his start in Memphis all the way back in 1985. They won that night, with Borden setting Allin up to get the pinfall. He still had it. And after the bell rang, as he rose to his feet and lifted his head to hear the crowd’s applause, despite the sweat and exhaustion, the paint on his face remained pristine.

Get the ItList Newsletter

Author

Mike Piellucci

View Profile

Mike Piellucci is D Magazine‘s sports editor. He is a former staffer at The Athletic and VICE, and his freelance…