The Worst Plane Crash in History Was on Tenerife | HistoryNet

After a several-hour delay, the passengers on Pan Am 1736 were finally relaxing—their plane was getting ready to take off. Everyone on the chartered Boeing 747 was only minutes away from the beginning of a much-anticipated Mediterranean cruise vacation. In the first-class section, Caroline Hopkins finished letters she’d been writing to her two daughters. Next to her, husband Warren slipped a magazine into his seatback pocket. Through the cabin, other passengers settled back for what was supposed to be a short flight from Tenerife to Las Palmas in the Canary Islands, where everyone would be bused to their waiting cruise ship.

The Pan Am jumbo jet was moving slowly down Tenerife’s single runway when the passengers felt a sudden sharp swerve to the left. Back in the economy section, passenger Isobel Monda immediately looked out the nearest window. “The damn fool’s going to run off the runway!” she gasped to her husband Tony.

In fact, driving the jet off the runway was exactly what Captain Victor Grubbs and his first officer, Robert Bragg, were trying to do. The reason was simple and horrible: They had suddenly seen a KLM 747 speeding down the foggy runway directly toward them. Grubbs and his crew were trying desperately to get out of the way, even if that meant getting stuck in the soft grass adjacent to the runway.

But they didn’t make it.

On March 27, 1977, shortly after 5 p.m. local time, Pan Am 1736 and KLM 4805 collided on the runway of Los Rodeos Airport in the Canary Islands. More than four decades later, the crash remains the worst disaster in aviation history, killing 583 people, injuring dozens and creating lifelong trauma for thousands.

How could this have happened? The crash of a single 747 would have been terrible; a crash involving two jumbo jets was almost inconceivable.

A photograph taken just before the crash shows Pan Am 1736 on the Los Rodeos apron with the KLM 747, “The Flying Dutchman,” just in front of it, blocking its way. (HistoryNet Archives)

A photograph taken just before the crash shows Pan Am 1736 on the Los Rodeos apron with the KLM 747, “The Flying Dutchman,” just in front of it, blocking its way. (HistoryNet Archives)

In succeeding years, much of the blame settled onto KLM’s captain, Jacob van Zanten, who began his takeoff roll before receiving air controller clearance. But nearly a dozen mistakes and coincidences had to line up with dismaying precision in order for the disaster to happen.

Just for starters, neither of the airliners was even supposed to be on Tenerife, let alone on the same runway at the same time. Both were carrying passengers to the beginning of their vacations on Grand Canary Island. But on that Sunday morning, shortly before the scheduled arrival of the two 747s, a Canary Islands terrorist group set off a bomb in Grand Canary’s Las Palmas airport terminal, causing injuries and panic. A telephone threat to the airport switchboard made a reference to “bombs,” plural, and when that was relayed to airport officials, all incoming flights were postponed or diverted.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Thank you for subscribing!

While the ultimately unsuccessful search for a second bomb was carried out, a dozen incoming aircraft, including the Pan Am and KLM 747s, were sent to nearby Tenerife to wait until Las Palmas officials gave the all-clear. The search took hours, and those on board both airliners could be excused for becoming impatient.

Transcripts of the cockpit conversations later showed that the Pan Am crew members were able to fight that impatience better than the KLM crew. Trying not to jam up the airport’s small terminal building, Captain Grubbs, first officer Bragg and second officer George Warns kept the 380 passengers and 13 cabin crew members on board. After an hour or so, Grubbs invited anyone on board to have a look in the 747’s cockpit.

Dozens of Pan Am’s curious and bored passengers eagerly accepted the offer. A line of people waiting for a peek inside the 747’s cockpit extended through the second-floor lounge (the cockpit sat in front of that lounge), down a circular stairway into the first-class section, then back into the economy section.

“It wasn’t much fun coming in here, was it?” one of the passengers asked the flight crew. (Conversations were now being recorded on the 747’s cockpit voice recorder, which was recovered after the accident.)

“We didn’t know why we had to land, except they ordered us down,” Grubbs answered. “We told them that we could hold [above Las Palmas] because we had plenty of fuel.” His remark identified another of the day’s painful coincidences—if Pan Am had stayed in a holding pattern, the accident wouldn’t have happened. Grubbs then told and re-told successive cockpit visitors about the delay.

“Thank you all; it was a new experience,” one passenger told the crew. “Thank you,” Grubbs politely replied.

Meanwhile, back in the KLM plane, the crew had let their 234 passengers leave the aircraft and wander around in the Tenerife terminal building. While they waited, the KLM crew started fretting about strict Dutch government rules limiting overtime for flight crews—their scheduled continuing flight from Grand Canary to Amsterdam would push that limit.

“What are the repercussions” for cockpit crews who violate those rules, Willem Schreuder, the second officer, wondered.

“You’ll face the judge,” said a voice in the cockpit.

“Is it a question of fines or imprisonment?” Schreuder continued.

“At any rate it would mean revocation of your license for quite a while, and that means money,” Captain van Zanten answered.

Van Zanten then made an operational decision that made perfect sense but later proved disastrously significant: Wanting to use the wait constructively, he decided to refuel his jet.

More than four decades later, the crash remains the worst disaster in aviation history, killing 583 people, injuring dozens and creating lifelong trauma for thousands.

Ironically, just after the refueling started, Las Palmas airport reopened. So now, although everyone was anxious to leave Tenerife, KLM was temporarily immobile, waiting for the fuel trucks to finish. Several smaller passenger jets were able to taxi around KLM and onto the runway and leave Tenerife, but Pan Am, parked behind KLM on the apron and too large to scoot around, was immobile, too. And with the extra fuel, KLM had become tens of thousands of pounds heavier, meaning it would need more speed and more runway to get off the ground. The significance of that was now only minutes away.

Meanwhile, the fog got thicker and the visibility quickly decreased.

Well before the refueling had finished, KLM rounded up all the passengers who’d been browsing in the terminal and bused them back to the waiting plane. All, that is, except for Robina van Lanschot, an employee of a tour group based on Tenerife. She thought it pointless to fly to Las Palmas, then return to Tenerife with tourists. She decided to wait on Tenerife, so she asked a friend to send her luggage. Then she walked to a pay phone, called her boyfriend on Tenerife and was gone from the airport by the time KLM began taxiing. KLM’s 249 passengers and crew had just become 248.

Eventually the mother of three, van Lanschot said in a 2017 interview that she struggled with survivor’s guilt for many years over her spontaneous decision—a decision that saved her life.

Shortly before 5 p.m., the control tower gave KLM permission to start its engines, enter the runway at the northwest end, then move down the runway and leave it on the third turnoff, C-3. That would put KLM on the adjacent taxiway, from where it could continue to the southeast end. Then KLM was to swing back onto the runway for its takeoff run back to the northwest. Pan Am was about to start its engines, and would be given exactly the same instructions, following KLM.

But it didn’t work out that way. Both airline crews got confused about the runway exit they were supposed to use. Neither crew was sure if the ground controller had told them “first” or “third” runway exit—the two words have an identical “ir” sound in the middle. And C-3 required a difficult maneuver. Both pilots would have to turn their jumbo jets 135 degrees to the left from the direction of their taxiing to get onto C-3. Then each would turn back 135 degrees to the right to continue on the taxiway. By comparison, the C-4 turnoff was only 45 degrees from the direction of their taxiing—an obviously easier maneuver. This may have contributed to the confusion.

After several radio calls between KLM and the tower seeking clarity, the controller changed his mind and told KLM to simply continue to the end of the runway and do a “backtrack”—a 180-degree turn so that the jet was facing the direction from which it had just come.

The KLM crew did as directed, completing their swivel turn as Pan Am was entering the runway on the other end. As with KLM, the Pan Am crew was instructed to leave the runway on the difficult C-3 turnoff, again causing confusion in the cockpit. The voice transcripts showed that Grubbs and Bragg had trouble believing they weren’t supposed to leave at C-4.

The elements of the coming disaster were now in place:

- Two jumbo jets facing each other on the same runway, but unable to see each other because of the fog, with Pan Am 1736 taxiing directly toward KLM 4805.

- A KLM crew anxious to get off the ground, following its earlier conversation about strict Dutch overtime rules.

- Two cockpit crews who were having trouble understanding their taxi instructions from the tower.

- Fog that was so heavy the controllers in the tower couldn’t see either plane, and neither plane’s crew could see the tower or the other plane.

And this airport had no ground radar.

The next few minutes saw a series of missed and misunderstood transmissions between the jet crews and the control tower. In one exchange—in retrospect, horrendous—Pan Am’s crew even told the tower it was still on the runway. That transmission should have been audible in KLM’s cockpit, but at that exact moment an electronic buzz, known as a heterodyne, interfered with the transmission, so KLM’s captain didn’t hear it.

Oblivious to this cockpit drama, the passengers inside each plane were adjusting seats, putting away items and getting ready for the short hop to Las Palmas. Caroline Hopkins, gazing out her left-side window, had even seen the KLM jet taxi down the runway a few minutes earlier, when Pan Am was parked near the terminal. Isobel Monda finished reading a religious pamphlet a neighbor had given her before she and her husband left on the trip. She tucked the pamphlet into the seatback pocket in front of her. Later, she saw much significance in that simple act.

As Pan Am taxied slowly down the runway, the crew examined their airport map and struggled to find their assigned turnoff to get onto the adjacent taxiway. Bragg, the first officer, later said the fog was so heavy that they taxied past C-3 without noticing it.

Just before Pan Am passed C-3, KLM’s captain took the action that sealed everyone’s fate: He began his takeoff roll before getting permission from the controller. As first officer Klaas Meurs was finishing a radio confirmation with the tower of their post-takeoff flight instructions, van Zanten pushed the throttles and began rolling down the runway just after 5:06.

“Stand by for takeoff. I will call you,” the controller said—the most tragically misunderstood eight words in the history of aviation. Apparently van Zanten heard only the word “takeoff.” (It’s important to note that this instruction would not have been appropriate in the United States then or now—the word “takeoff” would have been used only when the actual permission was being given. “Taxi into position and hold” or “Hold your position” would have been the standard way to give this instruction. The Tenerife accident changed international guidelines about communications between controllers and cockpits.)

Yet, even with van Zanten’s unilateral decision, there would be one last opportunity to avoid the collision. Second officer Schreuder didn’t like what he (correctly) thought he’d heard on the radio. “Is Pan Am still on the runway?” he asked van Zanten, speaking in Dutch, as KLM picked up speed.

Van Zanten didn’t hear him clearly, and precious seconds were lost. “What did you say?” the pilot asked his flight engineer.

“Is he not clear, the Pan American?”

“Oh, yes!” van Zanten responded. The last words in the KLM cockpit, just before the impact at 5:06:49, were a horrified curse, when Pan Am suddenly appeared through the fog in front of them: “Oh, Godverdomme…”

Van Zanten pulled hard on the yoke and added power in a futile attempt to clear the Pan Am 747. He managed to get partially airborne, in the process carving a 68-foot groove in the runway with his plane’s tail. The ensuing collision killed everyone on board KLM 4805 and most of those on Pan Am 1736.

Pan Am had been struck at an angle because of that emergency left turn by Grubbs and Bragg. As a result, some sections of the 747 weren’t as damaged as those that had taken the full impact of KLM’s engines and lower fuselage. More than 100 Pan Am passengers were alive and some were even relatively unhurt at this point, according to later interviews. What followed was the next phase of this disaster: a frantic few minutes of evacuation by some of the passengers, and a stunned immobility by others.

Unlike the common “fight or flight” reaction, there is a third, dismayingly common response to emergencies: behavioral inaction—freezing, being unable to react. It’s been observed in many emergencies, including the 9-11 attacks. As one Pan Am survivor later described it, a disturbing number of passengers sat motionless “like deer caught in headlights.”

After the collision, the situation inside Pan Am 1736 required immediate action as fires and smoke filled the cabin. The first people to respond, other than the crew members, were those who’d been in crisis situations before—former military members, for example. (Importantly, others who quickly responded included those who said they’d looked at the safety cards and understood the cabin’s layout.)

Warren Hopkins, a World War II combat veteran, wasted no time. Despite bleeding from a deep gash on his head from falling debris, he immediately unbuckled his belt and told Caroline, “Let’s go!” His quick response motivated his wife and others nearby to move. Hopkins made his way to the doorway area, only to find that no slide was available because the doorway had been ripped apart in the collision. He paused, then leaped 20 feet down to the runway, managing to land on his feet but severing tendons in his right foot. Caroline followed, breaking her collarbone when she hit the runway.

Other veterans, despite their age, had similar quick responses. Tony Monda, another WWII veteran, directed his wife Isobel out an opening on the left side of the fuselage, then followed her after retrieving his carry-on bag (an action now strongly advised against). Although Isobel suffered injuries in the evacuation, Monda was remarkably unscathed. Still other veterans responded similarly. Retired U.S. Navy admiral Walter Moore guided his wife Beth out of the plane but then stayed in the cabin to help others—heroism that he paid for with his life.

Several less-injured passengers followed the example of passenger David Alexander. Cleverly, when he saw no easy exit through the side of the fuselage, he climbed up through a hole in the ceiling, then down to the left wing.

The scene outside the plane was chaotic, with huge orange flames and massive plumes of black smoke billowing from the destroyed Pan Am airliner. KLM 4805’s wreckage was engulfed in flames 400 yards farther down the runway. Despite their own injuries, Pan Am’s cockpit crew and four surviving cabin crew members did their best to guide passengers to safety. All later received awards from the National Transportation Safety Board for their professionalism.

At least 71 people on board—including the three cockpit crewmen, two observers in the cockpit and four flight attendants—survived and were able to get away from the burning fuselage. However, several passengers later died of their injuries, bringing the final total to 583 dead.

In addition to the change in international air controller wording referred to earlier, other safety changes in succeeding years included the expansion of a traffic light system to warn taxiing aircraft crews when approaching a live runway. And a team-based approach to flying, known as crew resource management, has become standard in the industry. Such a system might have encouraged KLM’s first or second officer to speak up more emphatically during those critical final moments on the runway.

In the years after the Tenerife crash, the island’s government completed a new airport—one with ground radar.

The Canary Islands disaster did more than generate a review of aviation standards. It also spurred the process of addressing the mental trauma of aviation accident survivors, thanks in good part to Dr. John Duffy, a former U.S. assistant surgeon general who’d gotten interested in the psychological effects of surviving an air crash. In 1978 he held a conference on the subject, and was often quoted in the media about the need to address long-term victim trauma. Up until then, post-traumatic stress disorder had usually been applied only to survivors of military combat.

Caroline and Warren Hopkins exemplified Duffy’s concerns. Both escaped from the Pan Am jet with what were considered minor physical injuries: severed tendons and a broken collarbone. While those injuries healed, the fears from that experience stayed with Caroline for the rest of her life.

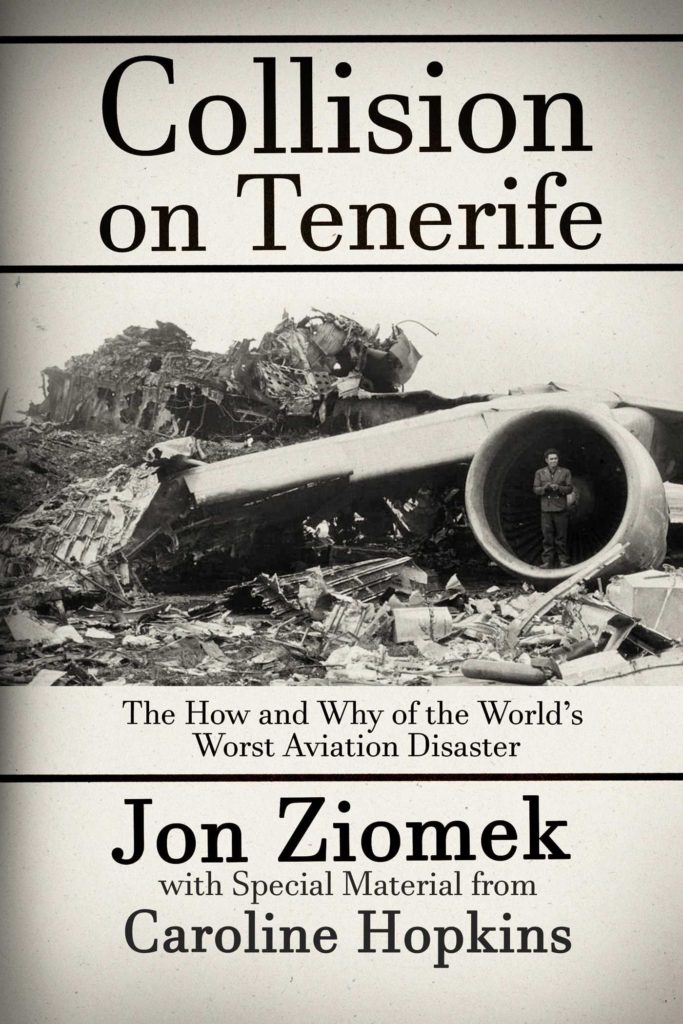

Collision on Tenerife: The How and Why of the World’s Worst Aviation Disaster

By Jon Ziomek, Post Hill Press, 2020

get it on amazon

If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.