Who Was Pericles, the Architect of the Athenian Golden Age?

Pericles, the first citizen of Athens, helmed the Athenian golden age. Through his policies and leadership, he guided and improved Athenian democracy and helped to establish the Athenian Empire.

The 5th century BCE represented the apex of cultural, political, and economic prosperity in one particular area in ancient Greece. Socrates began to establish the foundations of western philosophy. Playwrights such as Euripides, Aeschylus, and Sophocles were sponsored to create narratives that we still enjoy today. Phidias, the sculptor, created one of the seven wonders of the world, the statue of Zeus at Olympia. Herodotus began recording world history and Hippocrates, the father of western medicine, established the Hippocratic oath.

All of these people lived and breathed in one place at the same time: Athens. This era is sometimes called the golden age of Athens, however, it is also called by another name: the Age of Pericles. Named after the man who guided the city to prosperity, the first citizen of Athens.

Mục Lục

The Early Years of Pericles

Anaxagoras and Pericles, by Augustin-Louis Belle, 18th-19th centuries, via ancient-origins.net

Anaxagoras and Pericles, by Augustin-Louis Belle, 18th-19th centuries, via ancient-origins.net

Pericles was born in 495 BCE. His father Xanthippus was a wealthy Athenian politician and military leader. Pericles’s mother Agariste came from the very old and wealthy Athenian Alcmaeonid family. Her grandfather Clisthenes helped rid the city of the tyrant Pisistratus, and he established constitutional reforms that further strengthened Athenian democracy.

According to Plutarch and Herodotus, a few days before Pericles’s birth, his mother Agariste dreamed that she would give birth to a lion. This omen would be used time and again by Pericles’s political opponents to slander him. A few days later, when Agariste gave birth, it was revealed that Pericles had an oddly elongated head, which many took as the true meaning of her dream.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription

Thank you!

Pericles received the nickname “squill” because his head resembled a sea onion, and he became the target of many comic playwrights and poets throughout his tenure in Athens. Every depiction we have of Pericles depicts him wearing a helmet to cover his unique head shape and to celebrate his status as an Athenian military leader.

Bust of Pericles, 430 BCE, via Thoughtco

Bust of Pericles, 430 BCE, via Thoughtco

A son of privilege, Pericles received a good education. Pythocleides and the sophist Damon taught him music; Zeno taught him about the natural world; and the famous pre-Socratic philosopher, Anaxagoras, taught him philosophy. Anaxagoras and Pericles became very close and the young politician would often turn to his old tutor for advice and guidance. Plutarch also suggests that Pericles learned sophistry from Damon under the guise of music. Plutarch notes that many saw young Pericles as somewhat snobbish — another aspect of his character highlighted by his future political enemies.

Although he was a child of privilege, Pericles understood turmoil and the chaotic nature of the world. At the age of ten, his father Xanthippus was ostracized from Athens. Ostracism was a common political practice in Athens at the time and it often occurred when a politician was seen as too powerful or too great a threat to his rivals. An ostracized citizen was not permanently banished from the city. After ten years they could return with their social and financial status still intact.

Xanthippus did not serve the full ten years. A few years into his exile he was recalled to defend Athens due to the Persian invasion because he was seen as one of Athens’s best military leaders. Xanthippus acquitted himself when he led the Athenian navy to a decisive victory against the Persians at the battle of Mycale in 479 BCE, a battle that marked the end of the second Persian invasion of Greece. Xanthippus died a few years later, a hero who had ensured that his son could pursue a life of his choosing without the stigma of ostracism.

Athenian Politics

School of Athens, by Raphael, 1509-1511, via Apostolic Palace, Vatican City

School of Athens, by Raphael, 1509-1511, via Apostolic Palace, Vatican City

Before we can journey into Pericles’s rise to political power, a brief breakdown of Athenian politics must be given. Athenian democracy was divided into two main bodies: the Archons and the Strategoi. The Archons were the chief magistrates of Athens, as well as other Greek city-states, and they took charge whenever a king or tyrant was not in power.

The Archons had existed in some form or another for centuries before the 5th century and they always came in threes: the Archon Eponymous, the Archon Polemarch, and the Archon Basileus. Their length of service changed with time and history. They initially served for life, then for a decade, and by the time of Pericles, they only served for a single year. The emergence of democracy greatly diminished the power of the Archons, and in the 5th century, their role was mostly ceremonial, with a few minor civic responsibilities.

While the Archons represented an aspect of Athens’s past, the opposite was true for the council of the Strategoi in the 5th century. A Strategos was a military leader or general, and in Athens, a council of ten Strategoi managed the actual workings of the city. While the Archons were chosen by randomly drawing lots at the assembly, the Strategoi were democratically elected every year. In theory, all ten Strategoi were equal in power, however, in practice, those with more charm and political aptitude gathered more political power over the others.

Similar to in modern democracies, the Strategoi were often divided into two opposing political groups: aristocratic conservatives and liberal pro-democracy radicals. The conservatives hoped to limit democracy to the wealthy few, while the liberals wished to further bolster the democratic process and grant more power to the common citizens of Athens. This was the state of things when a youthful Pericles entered the world of democracy.

Rise to Power

Battle of Salamis, by Wilhelm von Kaulbach, 1868, via Historyhit.com

Battle of Salamis, by Wilhelm von Kaulbach, 1868, via Historyhit.com

As a young man, Pericles avoided public speaking and politics. Instead, he focused on his military career believing that this was his true calling. Pericles avoided politics because of his striking resemblance in both look and voice to Pisistratus, a despised former tyrant of Athens.

However, life takes people down unexpected paths and in his early 20s, Pericles entered the political arena. The earliest recorded act of Pericles’s political career was in 472 BCE when he sponsored a play by the famous Aeschylus, entitled The Persians. Here Pericles acted as a Choragus, a rich citizen who sponsored a state-commissioned play whether they wanted to or not. The role of assigning a Choragus was one of the few functions of the Archons and although it was randomly forced on wealthy citizens it appears that Pericles was rather keen to sponsor this particular play.

Aeschylus’ The Persians depicts the Battle of Salamis in which Themistocles led Athens to victory over the Persians. At the time Themistocles was the leader of the pro-democracy party and the play celebrated his achievements outright. The aristocratic faction led by Cimon saw Pericles’ willingness to sponsor this play as an indication that Pericles was siding with that political group.

Themistocles had a lot of enemies, but the greatest of them was Sparta, a close ally of Cimon. Both Cimon and the Spartans advocated for the wealthy few having all the power. Themistocles was ostracized and had to leave Greece entirely after Sparta accused him of a conspiracy against them. Ironically, Themistocles found refuge with the Persian king, Artaxerxes I, the son of the man Themistocles defeated all those years ago. Artaxerxes I welcomed the man talented enough to defeat his father and made Themistocles governor of Magnesia where he spent the remainder of his life.

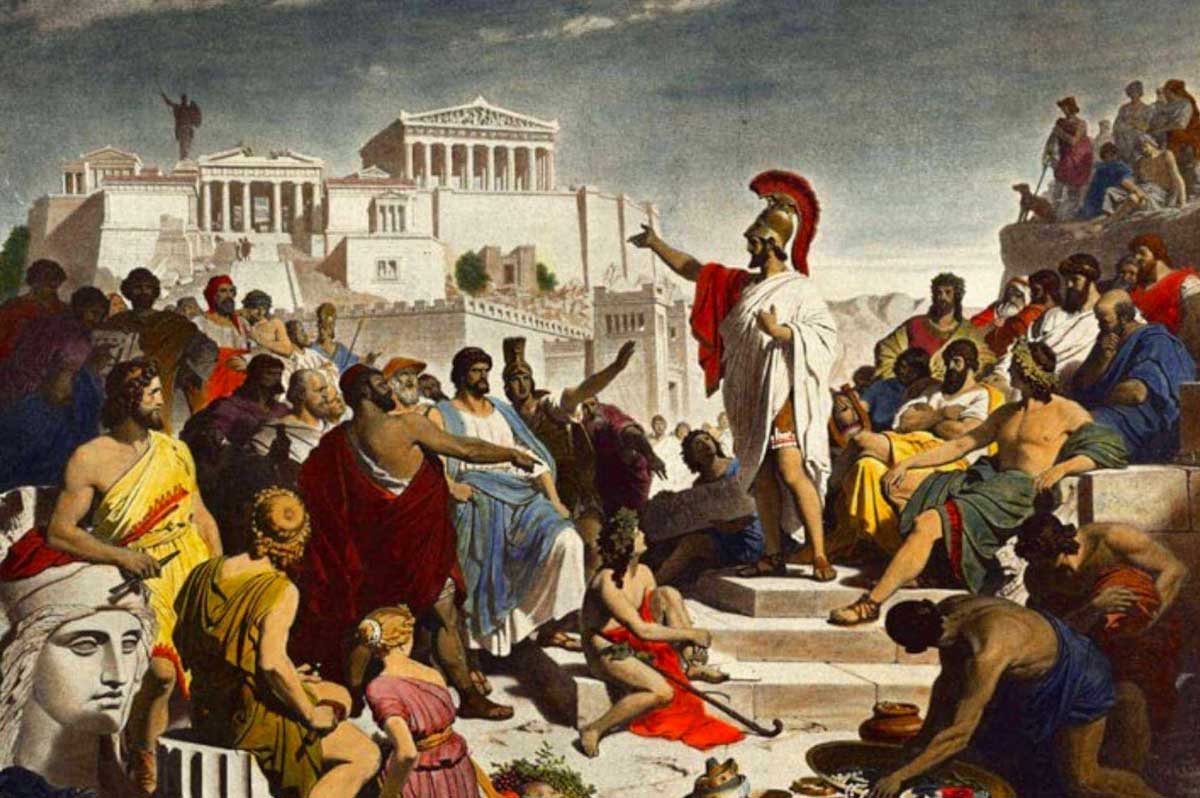

Pericles’ Funeral Oration, by Philipp von Foltz, 1877, via Cambridge University

Pericles’ Funeral Oration, by Philipp von Foltz, 1877, via Cambridge University

Throughout Pericles’s political career Cimon would be his greatest political opponent. Like Pericles, Cimon’s father Miltiades was a war hero who led the Greeks to victory at the Battle of Marathon. Cimon’s family had considerably more wealth than Pericles, and he used it to improve his public image by inviting citizens over every night for dinners. In contrast, Pericles is described by Plutarch as being anti-social and driven by his work.

Plutarch notes that throughout Pericles’s political career he rarely attended social functions or events. The only time Pericles did go to such an event, he went to the wedding of a kinsman of Euryptolemus. However, he left immediately after the ceremony was finished, tactfully avoiding the wedding celebrations.

Plutarch compares Pericles’s social interactions to the Salaminian galley: a special state galley in Athens only ever used for very special missions. Pericles reserved himself for special occasions and Plutarch mentions that one would only ever see the politician outside when he was on the road from his home to the political assembly.

Four Ostraka (pottery shards) nominating Pericles, Cimon, Aristeides, and Themistocles for ostracism, via Agora Excavations

Four Ostraka (pottery shards) nominating Pericles, Cimon, Aristeides, and Themistocles for ostracism, via Agora Excavations

Although Cimon had more resources, Pericles did not hesitate and began attacking his rival’s credibility during the assembly. Pericles claimed that Cimon was taking bribes from Alexander I of Macedonia, an ancestor of the great military leader who bears the same name. Cimon was tried and found not guilty; however, the scandal still damaged his political reputation and, in the end, despite Pericles’s attempts to rid the city of his rival, Cimon’s undoing was by his own designs.

Cimon had strong ties to Sparta and functioned as an ambassador who advocated a closer relationship between the two city-states. In 462 BCE Sparta experienced the Helot rebellion. The helots were slaves in Sparta, and while the Spartans focused on their military lifestyle, the helots farmed, fed, and looked after the Spartans. Cimon wanted to help his allies and eventually convinced the reluctant Athenian assembly to send over a thousand troops to aid them. However, when Cimon arrived the Spartan army told him to leave.

A mixture of pride and fear of the Helots learning about Athenian democracy led to their decision to turn away Cimon. Cimon returned home humiliated and Pericles had no trouble ostracizing the man in 461 BCE.

Bust of Cimon at the beach of Larnaca, Cyprus, via Harvard University Kosmos Society

Bust of Cimon at the beach of Larnaca, Cyprus, via Harvard University Kosmos Society

Without Cimon, Pericles’s political party became the most powerful in Athens. However, it was not yet led by Pericles himself but by his mentor Ephialtes, who tried to enact reforms limiting Athenian oligarchy and further strengthened democracy. But he was assassinated before he could see these reforms fully enacted.

Pericles’s enemies accused him of the murder, suggesting he did it to take full control of the party. Plutarch calls these claims baseless and Aristotle claims it was a man called Aristodicus of Tanagra. However, he provides no evidence as to why this may be the case. With one leader exiled and another now dead, Pericles easily consolidated his power and became the most powerful political force in Athens.

Bust of Aspasia, Roman copy of a Hellenistic original, via Britannica

Bust of Aspasia, Roman copy of a Hellenistic original, via Britannica

Pericles was married in his early 20s, but unfortunately, ancient historians never thought to record her name. We can assume that she derived from a wealthy Athenian background, and we know that she and Pericles had a loveless marriage that ended in divorce around ten years after they were married. Pericles and his wife had two sons, Xanthippus and Paralus. Both received extensive educations from their father but neither seems to have accomplished much. Likely, both men’s actions were unfairly compared to their father’s deeds. Not living up to both their father’s and the city’s expectations of them, they received the shared nickname the “Blitomammas”, a common epithet for a dim-witted person.

Nearly a decade after Pericles divorced his wife he met the love of his life — Aspasia of Miletus. The two never married but Plutarch tells us that they had a loving and tender relationship. Aspasia faced accusations of prostitution and of corrupting her partner’s decisions. However, this is likely mere slander. Aspasia seems to have been an incredibly charming and intelligent woman, gifted in rhetoric and public speaking, who only uplifted her rather anti-social partner’s social relations. The two had a son, Pericles the Younger, who was initially not considered an Athenian citizen because of his own father’s actions.

Aspasia of Miletus (c. 470-400 BC) with her lover Pericles, from La Civilization Vol. II, 1881, via Engelsbergideas.com

Aspasia of Miletus (c. 470-400 BC) with her lover Pericles, from La Civilization Vol. II, 1881, via Engelsbergideas.com

In 450 BCE, Pericles and Cimon had passed a law that clarified Athenian citizenship. Their new law dictated that Athenian citizenship could only be granted to a child if both their parents were Athenian citizens. Aspasia was from Miletus meaning that Pericles the younger could not gain any of the benefits of his father’s city.

Pericles’s older sons later died in a plague that swept through Athens. However, Pericles managed to change his law just before his death in 429 BCE, allowing children with one Athenian parent to become citizens. Unlike his two half-brothers, Pericles the Younger followed in his father’s footsteps and entered Athenian politics — joining the council of the ten Strategoi.

The Leagues of Athens and Sparta

Map of the Athenian Empire of the Delian League (478-431 BCE), via vividmaps.com

Map of the Athenian Empire of the Delian League (478-431 BCE), via vividmaps.com

When the Persians invaded Greece, Sparta was the unofficial and undisputed power behind Greece. They established the Peloponnesian league, uniting the disparate Greek city-states which defeated their foreign enemy. However, by the time of Pericles, states like Athens resented them, and their feelings were further amplified by the fact that mainland Sparta had no interest in liberating the Greek city-states still under Persian control within the Ionian Sea and Asia minor.

In 478 BCE Athens and many of the island states established their own league, called the Delian League. The league was named after the island of Delos, a neutral territory where the league members would meet and where they housed the league’s treasury. On the surface, the league was established to liberate Greek cities from Persian control, but in reality, it was set up to prevent Spartan expansion.

Over the years that followed, the tension between the Peloponnesian League and the Delian League grew. Athens rebuilt their defensive walls much to Sparta’s dismay, and the Spartans claimed that there was no need for Athens to do such a thing because Sparta would always be there to defend them. Athens went on to decree that it was free of Spartan hegemony and it began to expand the Delian league. The Delian league, in essence, became an Athenian empire, with all its member states contributing either troops or money to Athens, to ensure their protection. With no immediate military threats, Athens began denying troop donations and began to only accept monetary contributions. Within a few decades, the league consisted almost entirely of Athenian troops.

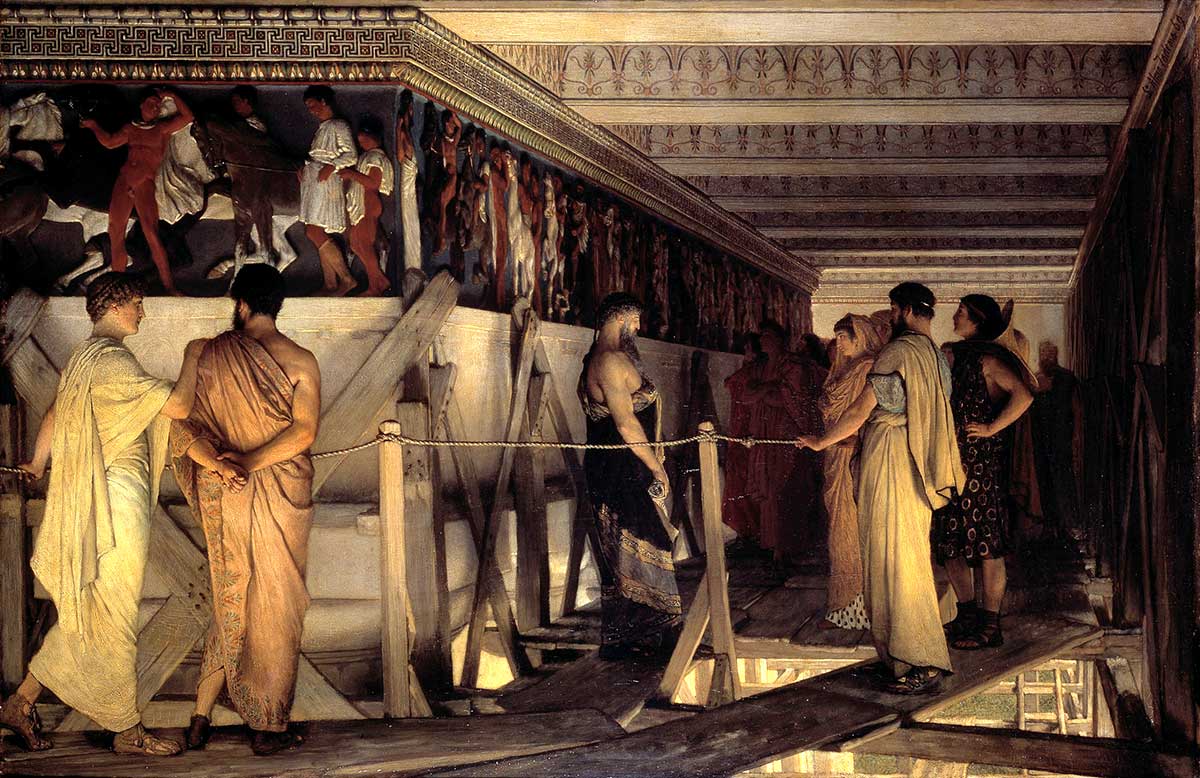

Pheidias and the Frieze of the Parthenon, by Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1868, via Researchgate.net

Pheidias and the Frieze of the Parthenon, by Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1868, via Researchgate.net

In 454 BCE Pericles moved the treasury from the neutral island of Delos to Athens. He argued that the treasury would be safer behind Athenian walls. In reality, Pericles used the money to fund building projects within Athens, the most notable being the buildings on the Athenian Acropolis. Pericles commissioned his old friend, the sculptor Phidias to act as surveyor-general of all public works. He had him create a magnificent statue of the city’s patron goddess, Athena, at the Parthenon. Pericles also commissioned a temple at Eleusis where the Eleusinian mysteries were celebrated, and the Odeum, a music theatre that imitated the King of Persia’s Pavilion. Pericles would go on to establish a yearly musical contest held at the Odeum, called the Panathenea.

This act of blatant corruption is arguably the greatest criticism Pericles received both in his time and in later ages. Thucydides, a relative of Cimon and rival of Pericles, attempted to have him ostracized for this corruption, but Pericles managed to publicly argue his way out of the situation. At the assembly, he agreed to pay for all the building projects from his own pocket, on the condition that they all bear inscriptions and dedications to him and no one else. This made the assembly hesitant and they quickly turned on Thucydides, ostracizing him.

The First Peloponnesian War

The Acropolis at Athens, by Leo von Klenze, 1846, via Wikimedia Commons

The Acropolis at Athens, by Leo von Klenze, 1846, via Wikimedia Commons

In 460 BCE the rising tensions between Athens and Sparta erupted in the First Peloponnesian War. War broke out when the city-state of Megara left the Peloponnesian League for the Delian League, resulting in a war between them and neighboring Corinth, one of Sparta’s closest allies. The Athenians were still focusing their efforts on liberating Greek city-states from the Persians and Pericles was initially hesitant to start another war.

However, Athens and Sparta began to engage in proxy wars through their respective allies and they only out rightly began to battle each other in 457 BCE at Tanagra. Sparta emerged as the victor of this battle but they had to retreat and consolidate their losses. Athens took advantage of this, regrouping and launching naval raids against Spartan allied ports.

This all changed in 454 BCE when Athens sent 200 ships to fight the Persians in Egypt. Athens suffered an epic defeat at the siege of Prosopis, which forced peace between Athens and Persia, known as the Peace of Callias. Athens’s defeat by the Persians left them vulnerable and many of the Delian League’s members began to revolt against Athens. Things only got worse in 447 BCE when Athens was defeated in a land battle by the Boatians, forcing Pericles to focus on navel prowess over land superiority.

Just like Pericles’s father Xanthippus, Cimon was recalled back to Athens early in 451 BCE to help fight the Persians. Pericles only accepted his rival’s return on the condition that Cimon was sent out to fight Persia at sea far away from Athens where Pericles’s rule would go unthreatened. Cimon helped negotiate peace with Sparta in 446 BCE, which was optimistically called “the thirty years of peace”.

The Death of Pericles

Plague in an Ancient City, by Michiel Sweerts, 1654, via the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Plague in an Ancient City, by Michiel Sweerts, 1654, via the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Even with Cimon’s peace established, Athens and Sparta still fought each other in proxy wars through their respective allies, such as in the Samian war of 440 BCE. This continued until 431 BCE when Sparta and Athens openly declared war on each other again. Pericles avoided land battles and instead decided to relocate all the people of Attica to the safety of Athens’s great walls. The Athenians managed to keep supplies coming in via their ports, supplying their people and thus creating a situation where they could survive a potential decades-long siege against the Spartans.

However, while Athenian ships kept Athens fed, they also brought an unknown plague to the city. It is estimated that this plague took out close to a quarter of the Athenian population. Among its victims were both of Pericles’s sons and in 429 BCE an unknown illness took the life of Pericles himself. Pericles left Athens in a state of turmoil, and the war with Sparta would be taken up by the likes of his adoptive son Alcibiades and the famous general Nicias.

Pericles bolstered Athenian democracy. He passed laws allowing any citizen participating in activities such as jury duty, to be paid for their time, thus eliminating the stranglehold of the rich on the assembly. He also blatantly stole money from his allies but he used this money to improve the city that he loved dearly. It is thanks to this selfish love that today we can gaze upon the Acropolis of Athens and marvel.